David Ross Locke (1833–88), the son of a shoemaker, was born in the small southern New York town of Vestal. Growing up in a working class family, Locke’s educational options were limited. After finishing the fifth grade, he became an apprentice—traditionally a 7-year engagement—in the printing trade for the Cortland Democrat. Sources differ on whether he began his apprenticeship at 10 or 12, or whether he completed the seven years or finished in five. Whichever is the case, Locke began his career as a newspaperman in 1850.

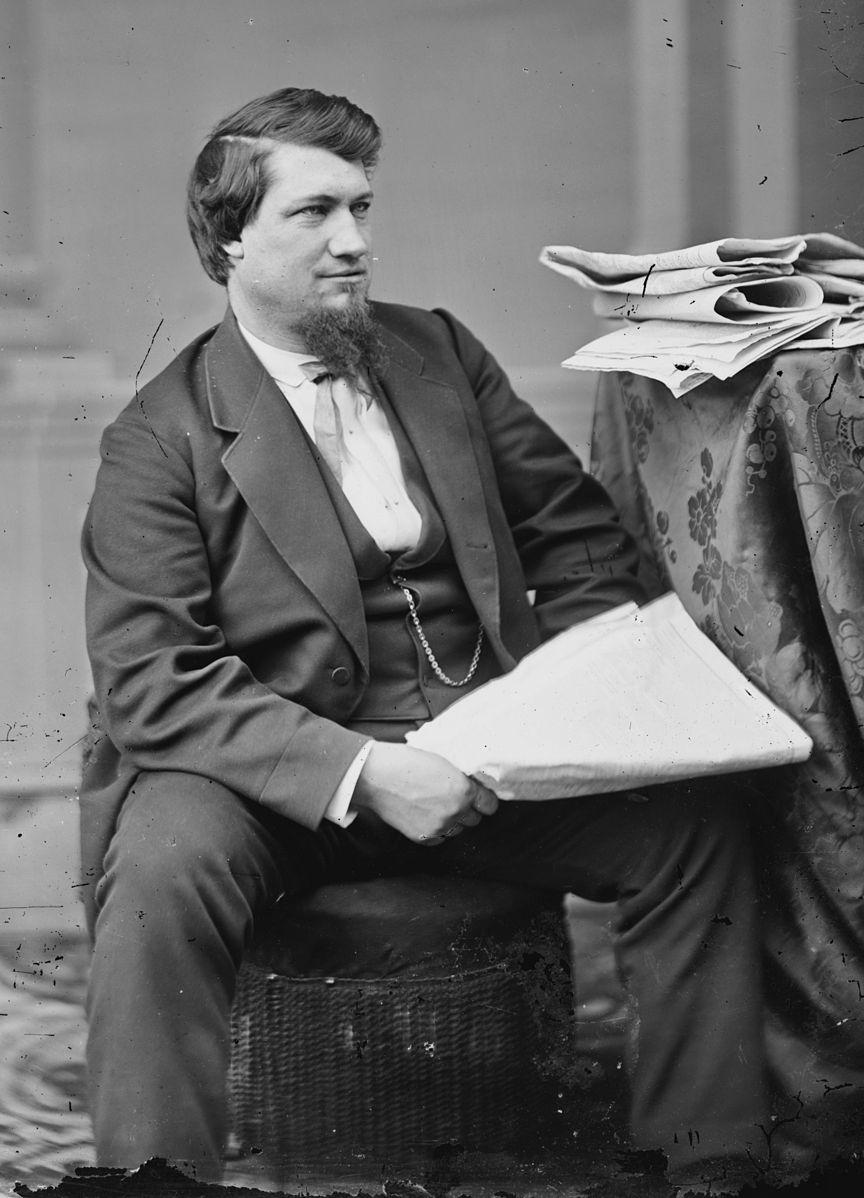

David Ross Locke, known for writing the satirical ramblings of a hypothetical Southerner, P. V. Nasby. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Public Domain