At some point in our lives we all face difficult choices that test our ability to judge right from wrong. David Matas, a Winnipeg lawyer who has focused his life and career on combating human rights abuses, has made the difficult choices. Whether he is representing a refugee or observing a foreign trial or election at the behest of the Canadian government, Matas has long been a champion of human rights.

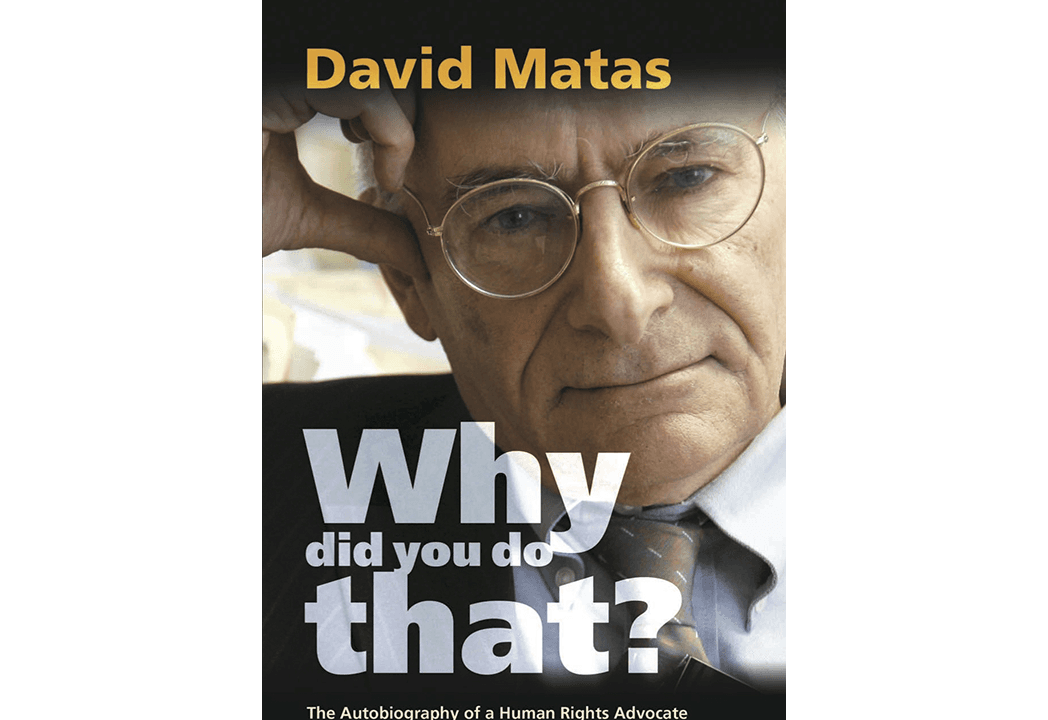

On June 16 in Ottawa, Matas launched his autobiography “Why did you do that?” The book explains his respect for human rights and his motivations for persevering through 42 years as a refugee and human rights lawyer and advocate. At 71, he travels tirelessly to combat injustices in Canada and abroad.

“I’m approaching this more in the need to help others, not help myself,” he said in an interview.

Matas was the first lawyer in Canada to practice immigration law and says that immigration law and refugee law were not taught when he was in university.

He dabbled in politics by running for office three times from 1973 to 1984. He chose a career in human rights advocacy over politics to enable action in community affairs when he realized that politics is partisan but human rights are universal.

Holocaust and Human Rights

Early in the book he focuses on the Holocaust as an example of egregious human rights abuses and explains how it changed the face of human rights around the world.

“I focus on the Holocaust so people get to see what this global consciousness of human rights is and where it came from,” he said.

After the Holocaust, he explains, “A whole sequence of international human rights instruments were developed, which impose duties on individuals—not just states—and grant rights to individuals—not just states.”

“The human rights revolution is then a dual revolution: a rights revolution and a humanity revolution,” he writes. “The Holocaust, more than any other, generated the humanity revolution.”

“The Holocaust, and later apartheid, were glaring manifestations of oppression through law. Lawyers have an especial responsibility to oppose repression through law.”

Subsequent chapters detail different types of legal and advocacy work he has participated in, and the Holocaust is referenced to explain these complex issues, drawing comparisons to events that have played out in similar fashion to the Nazi annihilation of Jews during World War II.

Difficult Investigation

One chapter, “The Killing of Falun Gong for Their Organs,” explains the comprehensive and difficult investigation he undertook with former MP David Kilgour to determine the validity of early reports of Falun Gong prisoners of conscience being used as a living organ bank to supply China’s lucrative organ transplant trade.

The difficulties in getting information were many as the victims were killed in the organ harvesting process, government records of transplants are not made public, and the hospital staff was not likely to admit to the illegal activity. Matas writes that he and Kilgour were helped by Chinese lawyer Gao Zhisheng who subsequently lost his license to practise and was imprisoned and tortured for his efforts. By 2006, they found the allegations to be true and published their findings in a report, followed by another report and then, in 2009, the book “Bloody Harvest.”

Matas also talks about international human rights law and the reasons why it can and should be applied to local human rights cases. “What I review in the book is the value of bringing more international human rights law into court litigation, into the practice of law.”

The book exhibits a comprehensive understanding of the needs of refugees, of bringing war criminals to justice, the need for hate speech laws, and advocating for victims of international human rights violations. His contributions are both hands-on and scholarly as he has published numerous reports and is frequently consulted for his expertise.

Encouraging Involvement

Matas knows well the terrain of human rights. He works with a wide range of clients and rights cases and serves on several boards. He also works with many international human rights non-governmental organizations, such as Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, B'nai Brith, and others.

One goal of writing the book, he explains, is to encourage people to become involved in human rights issues.

“Part of what I’m trying to do through that book is to mobilize that sort of effort where people are not touched or affected personally and yet they still should be involved,” he said.

“That’s what human rights is—it’s solidarity with humanity as a whole, and I think it’s important to reach out beyond your community, your culture, even your continent to show solidarity with victims of those whom we have nothing in common except humanity.”

Kilgour, also a lawyer, was one of many of Matas’s legal colleagues at the June 16 launch.

“I bought this in Paris actually,” he said, referring to the book “I’ve read every word in the book, it is absolutely fantastic. You will enjoy every page, every paragraph. There isn’t an issue in here that he doesn’t touch on.”

Matas was appointed to the Order of Canada in 2009, and was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize (along with Kilgour) in 2010. The autobiography is his 11th book and is currently topping the paperback non-fiction bestseller list in Winnipeg.