President Franklin D. Roosevelt wasn’t interested in going to war in the late 1930s and early ‘40s when Europe was under siege by Germany. He signed the Lend-Lease Act as a way of supporting England with supplies, but he resisted Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s pressure to send troops.

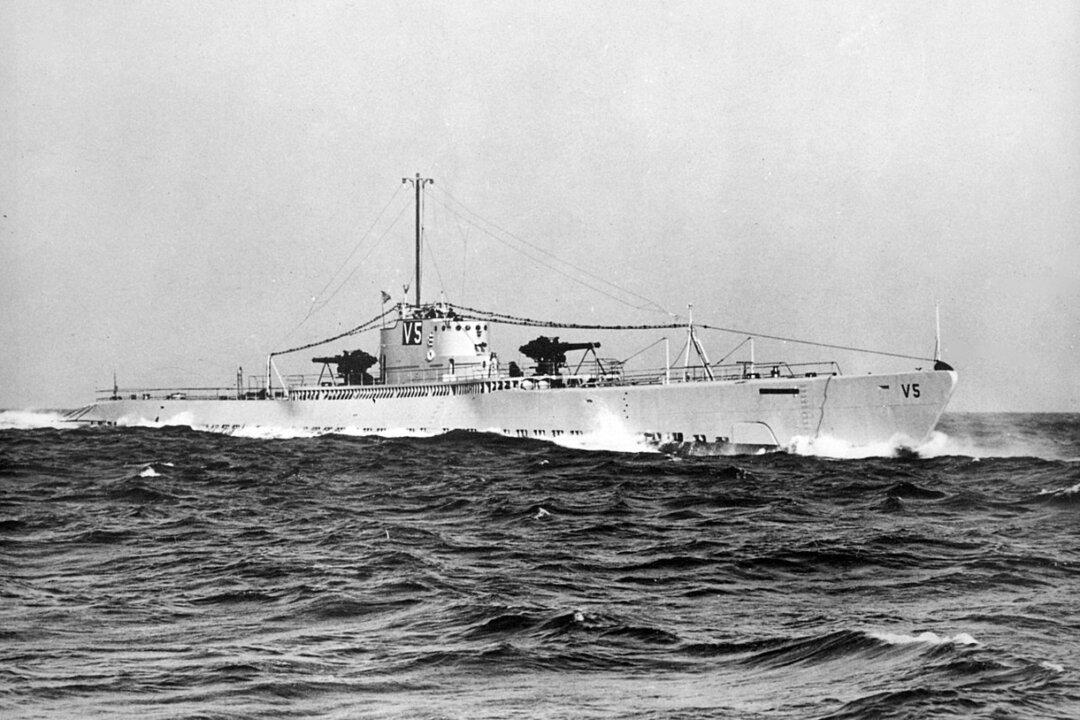

The bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese on Dec. 7, 1941, was a game changer, catapulting the United States into the conflict in both Europe and the Pacific. On Dec. 8, 1941, the Japanese attacked Manila on Luzon island, as well as several other islands, in the Philippines.