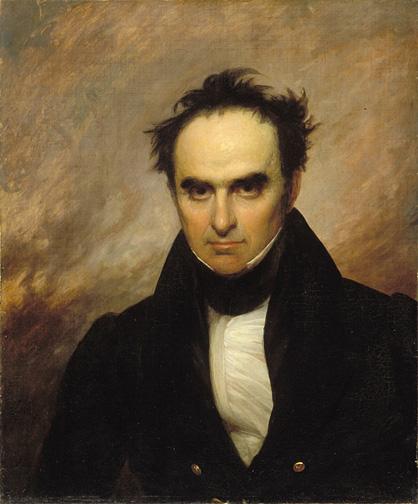

Three talents set Daniel Webster (1782–1852) apart from most of his fellow senators.

The first was his extraordinary memory. At age 15, ordered by his tutor to memorize 100 lines from Virgil by the following day as punishment for shirking his studies, Webster repeated the lines word for word and then offered to recite another 100 lines. This incredible capacity for memorization would prove crucial in an age when a speech might last hours.