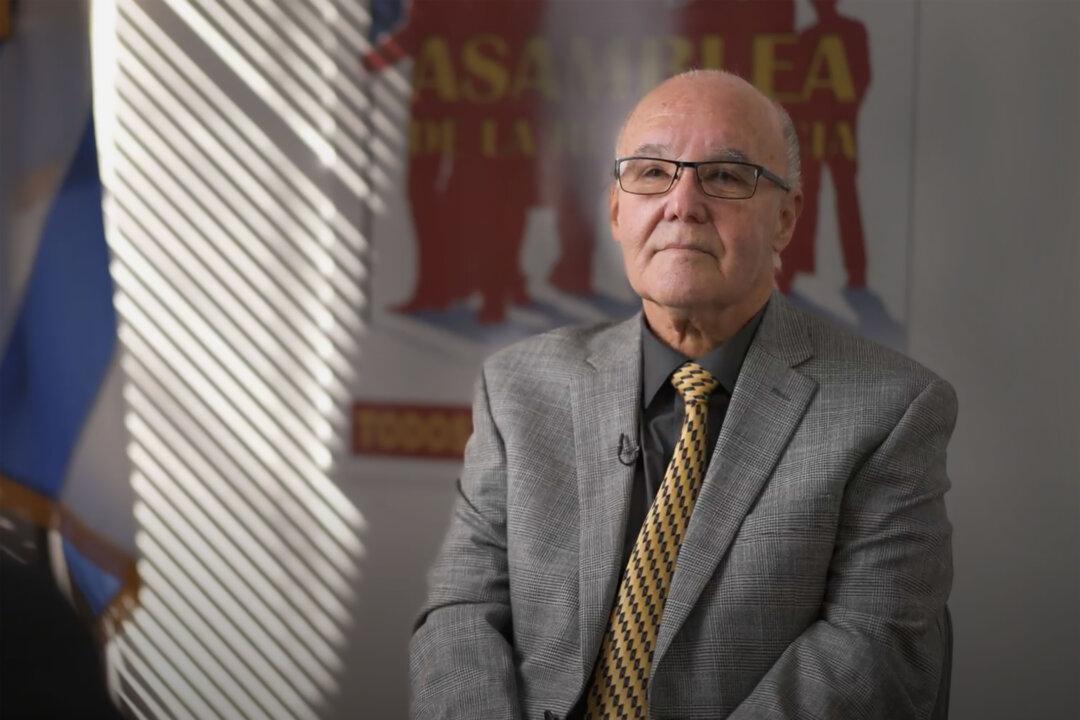

When Fidel Castro led the Cuban Revolution, he declared that he was not a communist. But when he came to power in 1959, he proved to be one of the staunchest advocates for the ideology. Luis Zuñiga, born in Havana 11 years before Castro’s coup, was never enchanted by Castro’s or communism’s promises. He instead worked to resist and possibly overthrow the new regime. His so-called “counter-revolutionary” activities resulted in imprisonment.

Zuñiga is now a prominent voice in the world for freedom and democracy, but he first had to secure his own freedom. He had to escape from Castro’s Cuba.

The Plan

“I was scared. I decided to do it and that was it. I did not want to spend my life in prison.”

It was 1969. Castro had been in power for a decade. By now, both dissenting revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries had been executed, imprisoned, or exiled. The Bay of Pigs Invasion had long since failed. The Cuban Missile Crisis had concluded seven years prior. The island nation was now a bastion of totalitarianism.

Zuñiga, the young, 22-year-old anticommunist, sat in a prison cell in the middle of a country that had itself become a prison. He had been appropriately labeled a “plantado”: a political prisoner who refused to succumb to communist reeducation and indoctrination.

Enduring solitary confinement, starvation, and beatings, Zuñiga spent two years languishing in Manacas Prison. In two months, he formulated his escape plan.

The first phase of his plan was reaching the infirmary in Santa Clara; but he needed a reason to go there. “A doctor friend told me to put pressure on my thigh and tap on it constantly, but don’t leave any bruising,” he said. “It will look like an infection, like lymphangitis.”

Zuñiga tied a piece of cloth around his thigh to swell and discolor his leg. The prison provided him antibiotics to remove the “infection.” Zuñiga kept at it; prison officials decided to move him to the infirmary. Phase one in a long and dangerous adventure had succeeded.