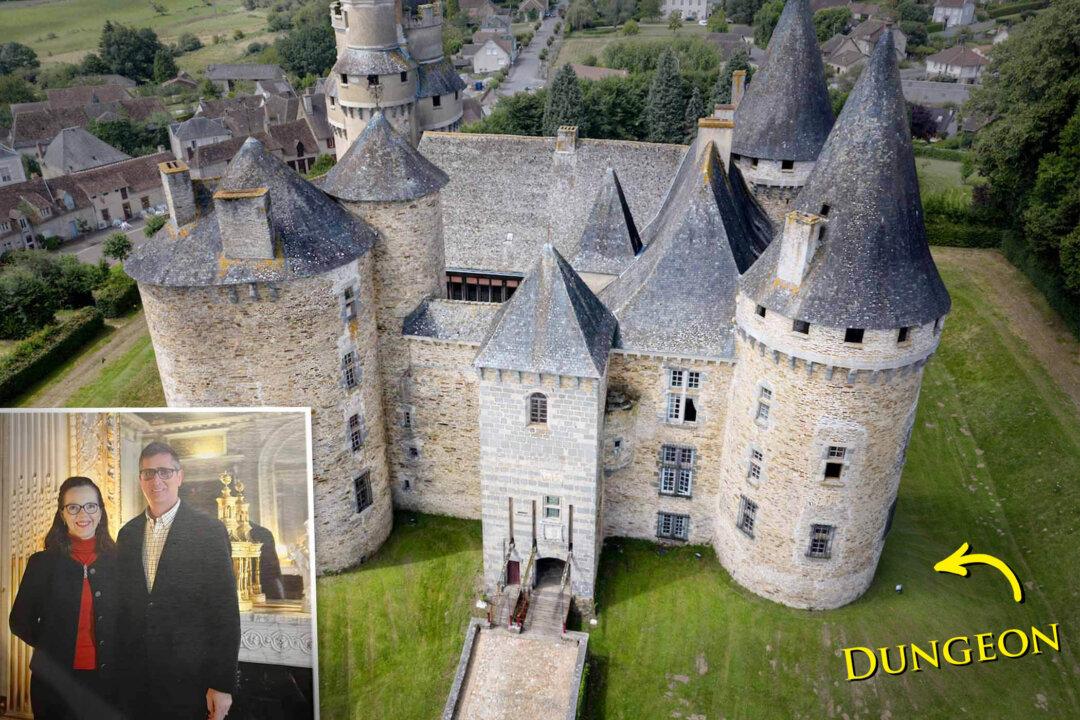

There is a very old, elegant, French castle in a small village five hours south of Paris, about half that distance north of Toulouse, where the hosts who live here, whose family has lived here for centuries, welcome guests to be transported into the past.

It’s called the Château de Bonneval, after the family who has called this place home for over a thousand years.