ITHACA, N.Y.—Richard Johnson can see right through the masterpieces of Rembrandt and Van Gogh.

The Cornell University electrical and computer engineering professor is a digital art detective, able to unlock the mysteries of a work’s age and authenticity by analyzing its underlying canvas or paper.

Using high-resolution X-ray images, the 64-year-old academic can actually determine if paintings came from the same bolt of hand-loomed canvas, each of which has a varying thread density pattern that can be as unique as a fingerprint. Linking multiple pieces of canvas to the same bolt can shore up arguments for authenticity and even put works in chronological order.

It’s a valuable service to world-class museums that comes through the unlikely cross-pollinating of traditional art history and contemporary computer science.

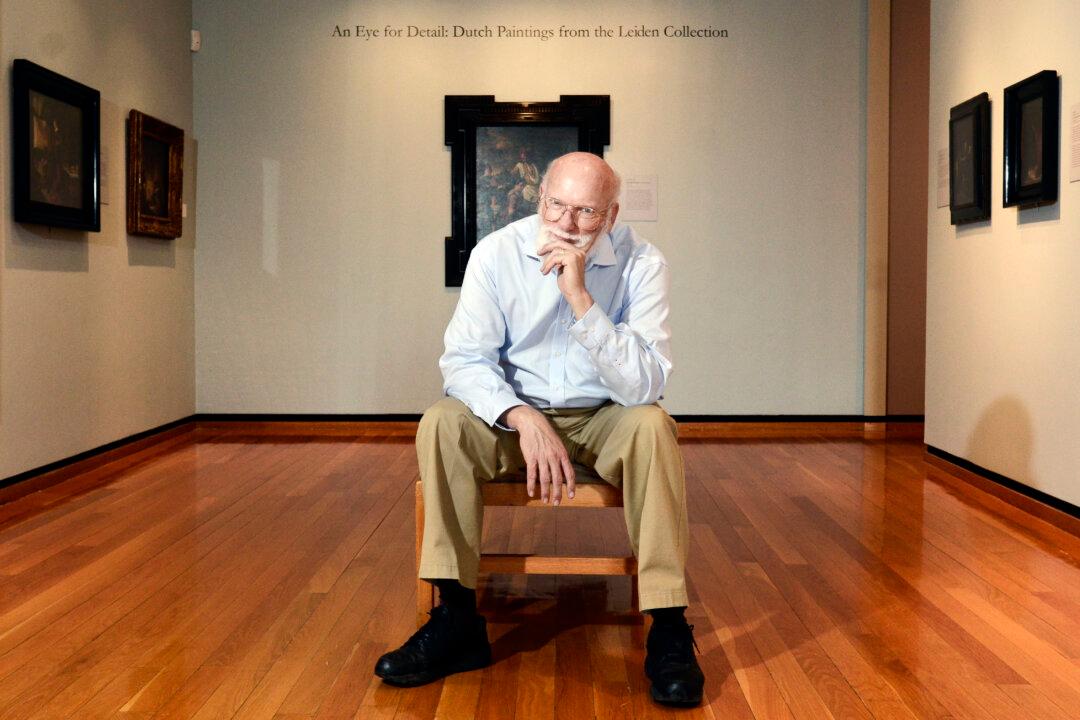

“By mixing the two groups we’ve been able to do more than either group had been able to do separately studying the paintings,” Johnson said in a room full of Dutch paintings at Cornell’s Johnson Museum. “We’re not trying to replace the art historian, we’re trying to extend their reach.”

Tech Background

Johnson is a tech whiz and an art lover—the rare person able to speak with authority about Rembrandt’s brush strokes and adaptive feedback systems theory.

Although he didn’t make his first visit to an art museum until he was a student on fellowship in Germany, the rooms full of Rembrandts left him thunderstruck.

Johnson melded the two worlds in 2007 with a stint as an adjunct research fellow at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. He began examining high-resolution X-ray images of the canvases used by the 19th century master.

Eventually, Johnson and Rice University professor Don Johnson (no relation) developed digital “weave density maps” of canvases that added computational power to what had been a painstaking process that required scholars to study small samples with magnifying glasses.