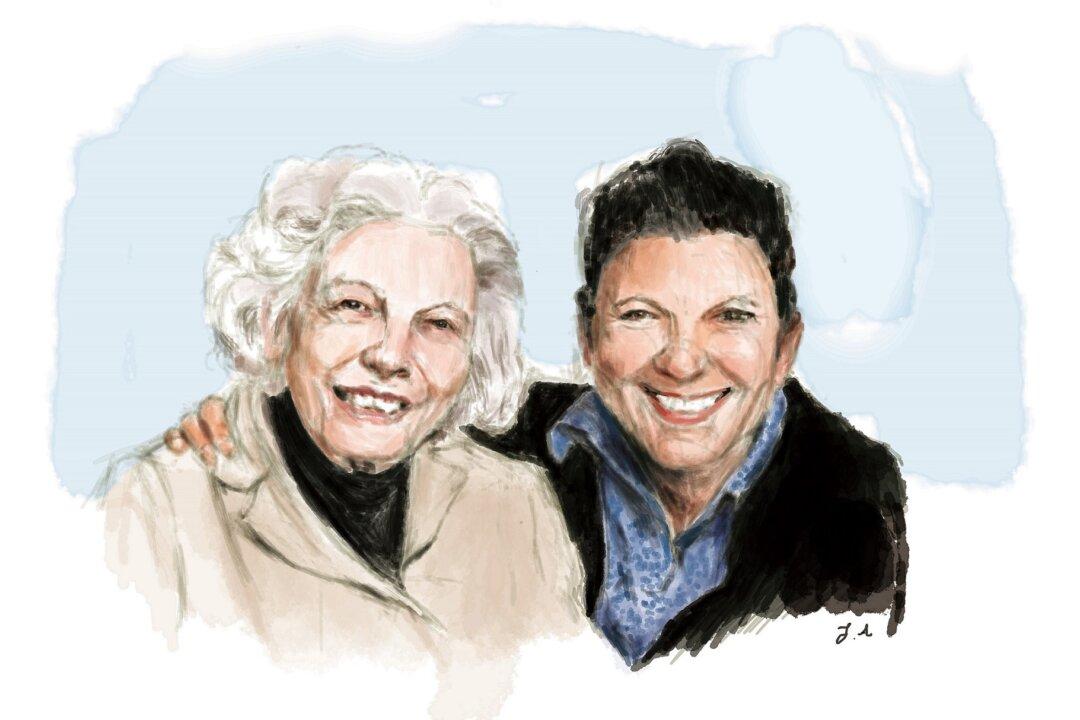

My beautiful 91-year-old mother stood in the kitchen staring at the onion in her hand, not knowing what to do with it. She was a few years into living with dementia and had recently started divesting all she wouldn’t need in the next life. Reading, writing, knitting, her favorite TV programs, conversations with friends—all had gone. On that day, her encroaching incapacity also claimed cooking.

Providing had been so essential to my mother’s mothering that both she and I lost much that day. I could barely see her through my tears as the realization that she could no longer care for herself, let alone me, hit home.