The Azores archipelago is about 1,000 miles off the coast of Europe, about a third of the way to North America across the Atlantic. The islands belong to Portugal, and the official historical record has long held that they were uninhabited until Portuguese expeditions colonized them in the 15th century. But a controversial alternative theory is gaining ground.

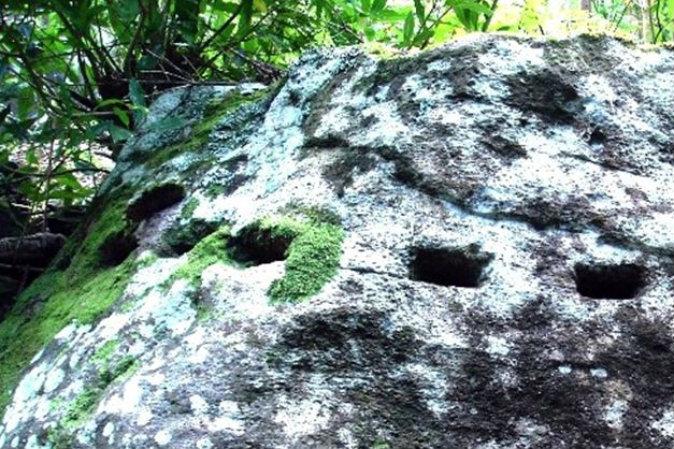

Some experts, including the president of the Portuguese Association of Archaeological Research, Nuno Ribeiro, have said rock art and the remnants of human-made structures on the islands suggest the Azores were occupied by humans thousands of years ago.