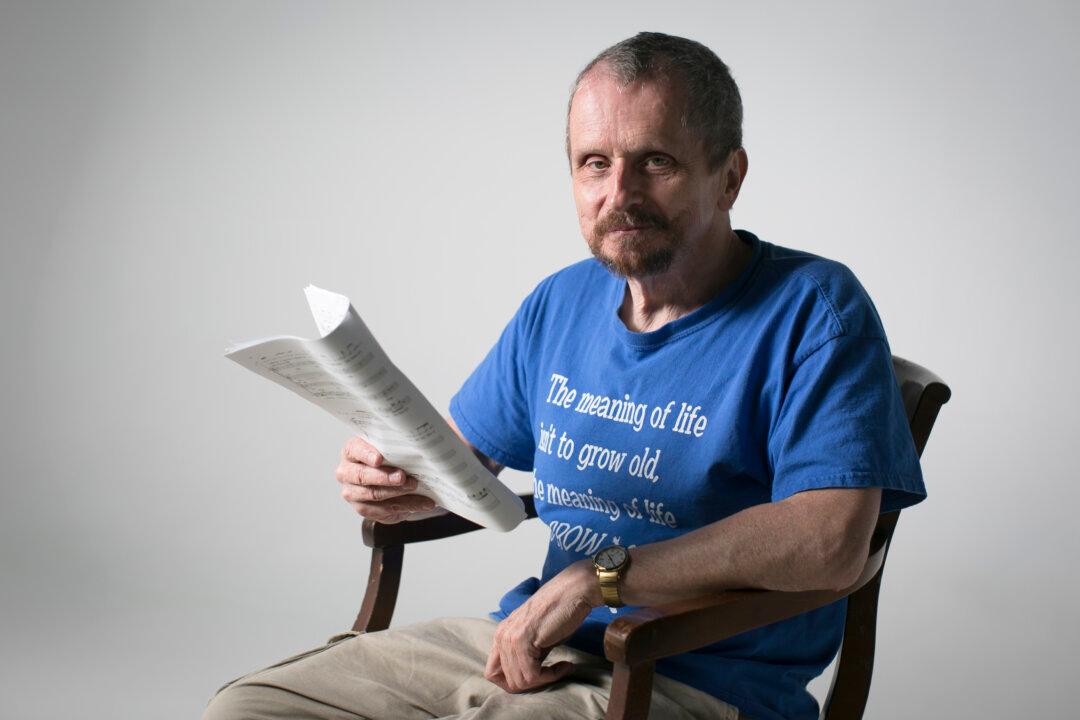

Composer William Vollinger writes deeply humane works: Hearing his song for soprano and clarinet, “The Child in the Hole,” we ache for a small boy who escaped the Holocaust by living three years in a dugout hole in Poland. To an unaccompanied baritone taking the role of Stalin from an iconic poster, we cringe at the dictator’s madness. And, in his choral piece “The Torrent,” the setting of a poem by Jenny Joseph, the life force of God’s majestic power pours forth but eventually trickles down to a stream of ordinary human kindness, and we first stand in awe and then melt in warmth.

For this composer, who anchors his life in faith, the classics have the power to humble us. The classics can help us “get beyond ourselves,” ourselves in the sense of our own egos, and remind us to respect those who contributed before us, Vollinger said in a phone interview on June 9.

“Such humility is good, as it doesn’t tear down but builds up, creates rather than destroys. Humility is, after all, the truth!” he said.

The truth of humankind’s connection to and dependence on God is found in all of Vollinger’s favorite classic works.

He listens to Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus” as though it were an addictive drug: “It’s joyful in a way that tells you God isn’t purple, but golden!”

He likes that the trumpets wait before entering, and “the sudden quiet of ’the kingdom of this world,‘ followed by a leap of a 10th, all those reiterated, rarefied ’King of Kings’ and ‘Lord of Lords,’ and the jump-for-joys at the end!” he said in an interview in Fanfare.

Vollinger respects Bach most and considers him a consummate musician able to use both his right and left brains—both the spiritual and intellectual parts—to create. “Bach wrote God’s music,” he said.

Haydn, though, is his favorite composer. Funny, clever, original, Haydn’s characteristics remind Vollinger of himself. But, quite simply, Hadyn’s music makes him feel happy.

As a testament to his admiration, he set several of Haydn’s quotes about music, God, and the creative process to music in the piece “Some Things That Haydn Said.”

Of visual artists, his favorite painter is Rembrandt, whose work, he believes, is painted with agape love. Rembrandt’s strength was to paint “ordinary people, giving them an extraordinary inner beauty,” irrespective of whether they were black slaves or Jews—unheard of in Rembrandt’s time.

There is no easy way to categorize Vollinger’s own music. We can say that he often lets words lead the music. We can say that he uncovers compelling historical events, as in his yet unperformed opera, “The Witnesses.” It tells the true story of a pastor forced by communist police to shoot to death two women from his church in China during the Cultural Revolution.

We can say that he believes whole-heartedly in George Balanchine’s famous saying, “God creates, I arrange.”