A recent Publishers Weekly newsletter listed “10 Essential Books About the Immigrant Experience.“ None are about my kind of ”immigrant experience,” nor have they ever been.

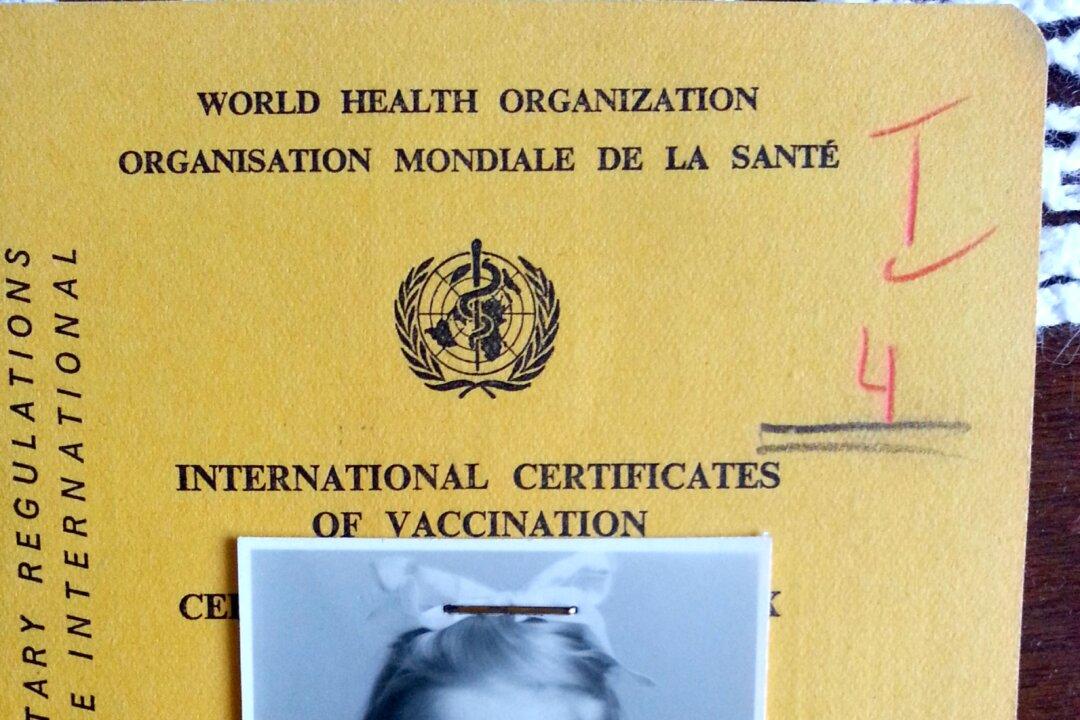

When I escaped Yugoslavia at age 2 with my parents, I was too young to remember what it was like to live under communism.