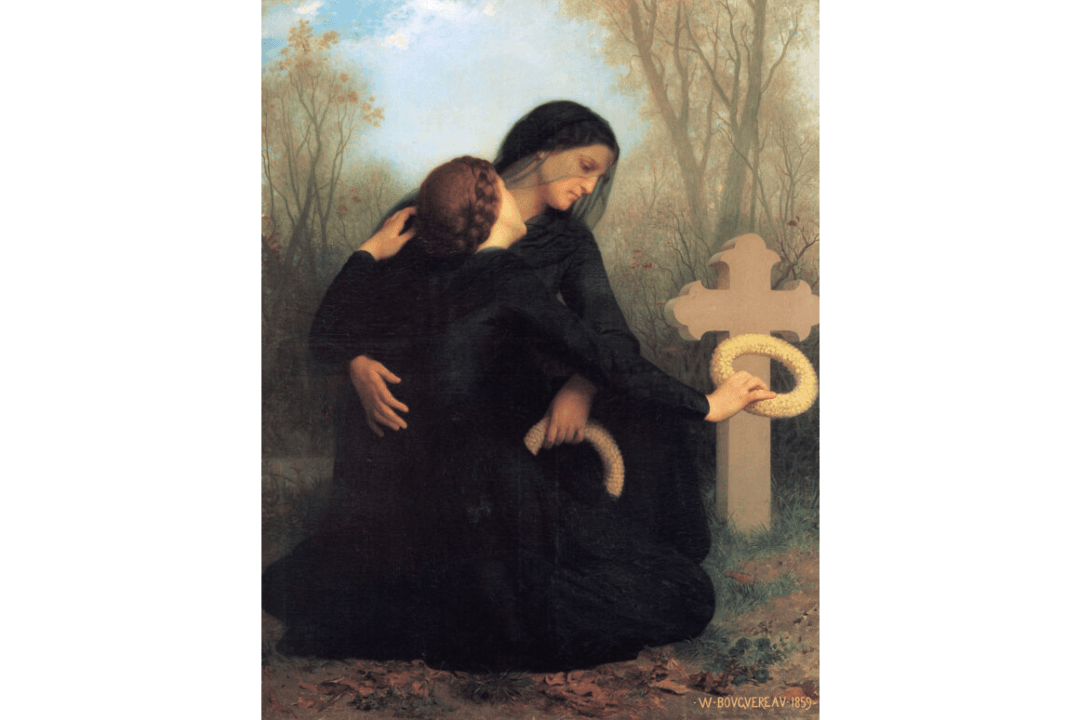

As discussed in Part 1, writer Joan Didion died in 2021 and left behind a lifetime of writing on culture, literature, family, and loss. Her 8,000-word essay “After Life” was published in September 2005. It focused on life, death and grief, after her husband John Dunne’s death in 2003, and the death of their only child Quintana in August 2005.

Didion finds meaning not only in the spectacular, but also in the everyday, including as wife and mother. She recalls with fondness, even pride, “Setting the table. Lighting the candles. Building the fire. Cooking … clean sheets, stacks of clean towels, hurricane lamps for storms, enough water and food to see us through whatever geological event came our way.”