A 1989 fatwa, or religious edict, by Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini, ordered the killing of novelist Salman Rushdie for his allegedly blasphemous novel “The Satanic Verses.” In 1998, Iran ended support of it. Libertarians soon condemned the cultures that forced Rushdie into hiding. They have since condemned the weak-kneed support offered to freethinkers worldwide when threatened by fundamentalists.

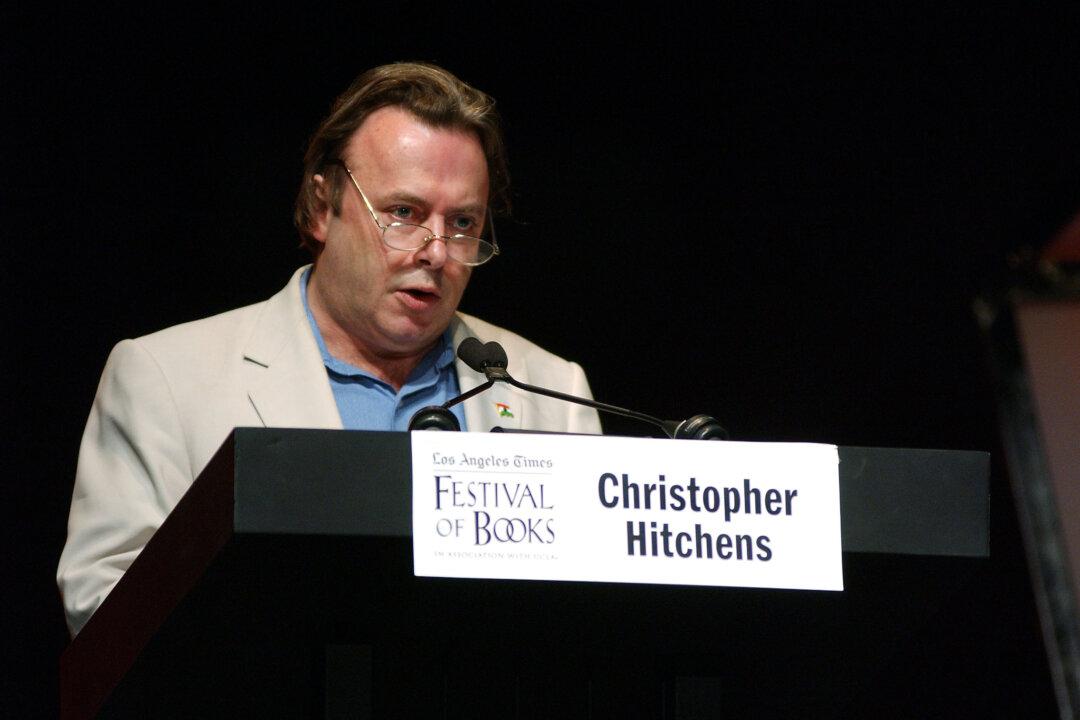

Journalist-writer Christopher Hitchens (1949–2011) marked the fatwa’s 20th anniversary with his essay, “Assassins of the Mind” (2009), which critiques the fatwa as “the opening shot in a war on cultural freedom.”