Part 2 looks at how freedom of expression can be destructive if used without restraint.

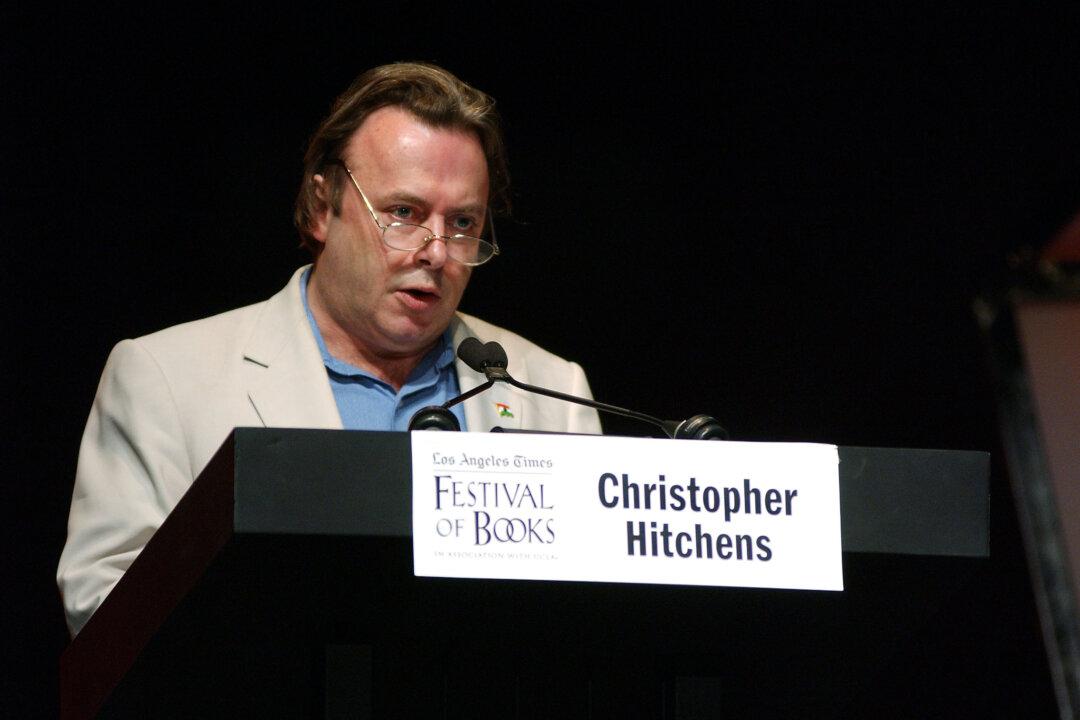

As discussed in part 1, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued in 1989 a religious edict, or fatwa, calling for the killing of novelist Salman Rushdie for writing “The Satanic Verses.” In his essay, “Assassins of the Mind” (2009), Christopher Hitchens (1949–2011) calls out this fanaticism as “the opening shot” in a war on freedom of expression.