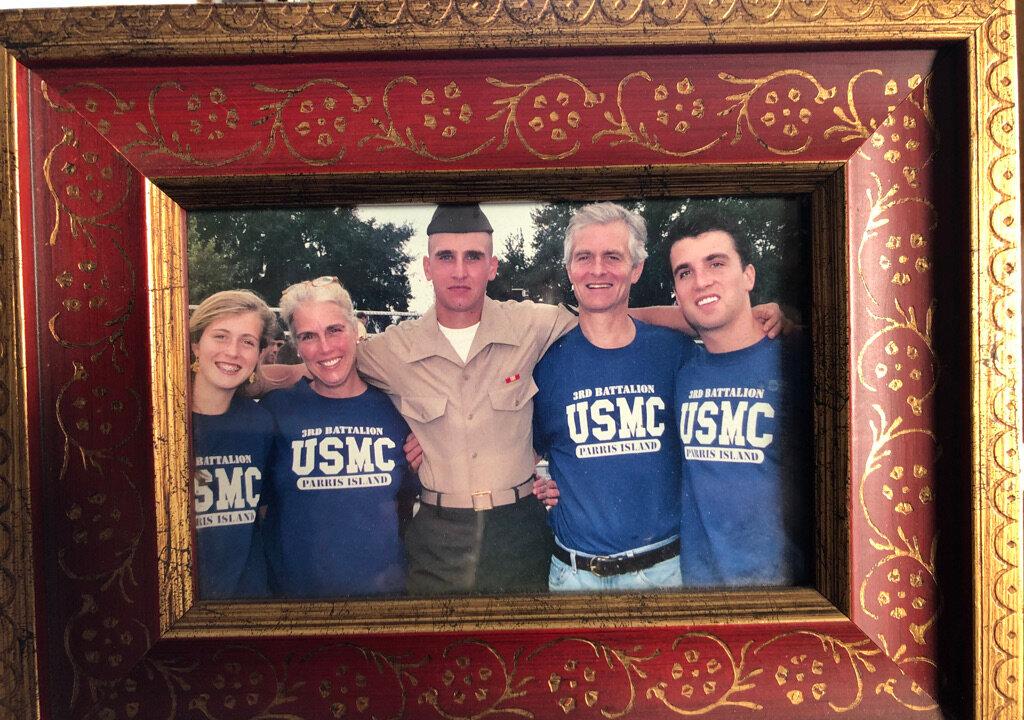

What does the fast-approaching Veterans Day mean to me and to the thousands of other parents who are missing their sons? What does it mean to me, the father of a homeless veteran, that the country will be honoring those who have served in our armed forces—those who survived the wars, and those who died in them?

There’ll be television, print, and radio interviews with the last surviving veterans of World War II; interviews with veterans who saw action in the jungles and rice paddies of Vietnam; and interviews with families who lost their sons in our more recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.