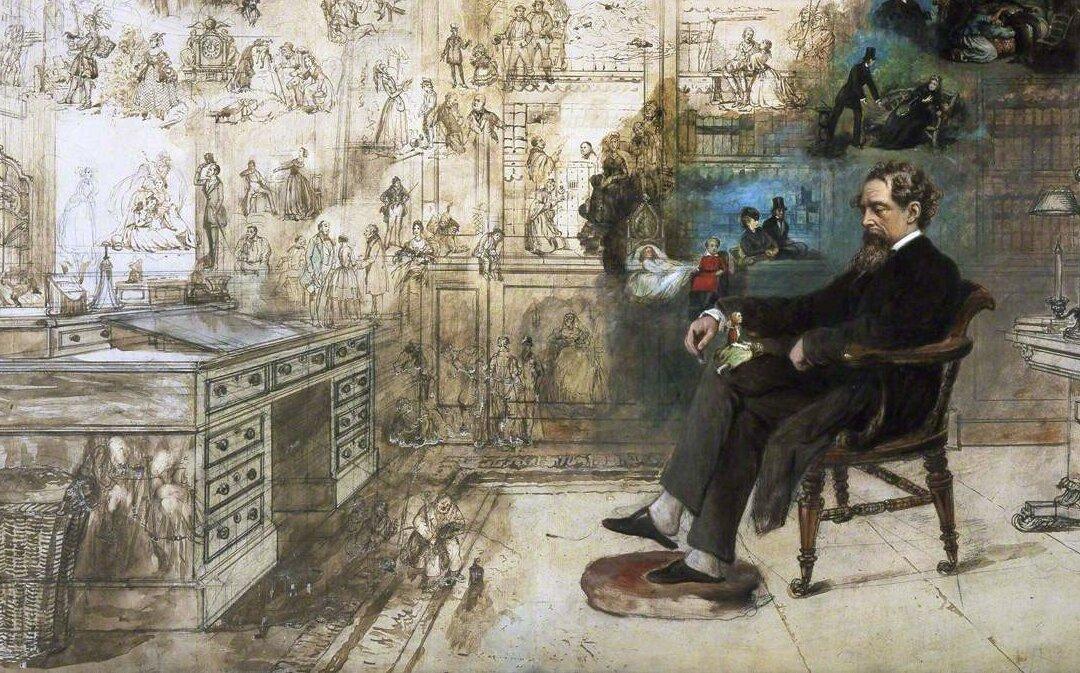

When Charles Dickens died on June 9, 1870, newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic framed his loss as an event of national and international mourning. They pointed to the fictional characters Dickens had created as a key part of his artistic legacy, writing how “we have laughed with Sam Weller, with Mrs. Nickleby, with Sairey Gamp, with Micawber.” Dickens himself had already featured as the subject of one piece of short biographical fiction published during his lifetime. Yet, in the years following his death, he would be increasingly appropriated as a fictional character by the Victorians, both in published texts and in privately circulated fan works.

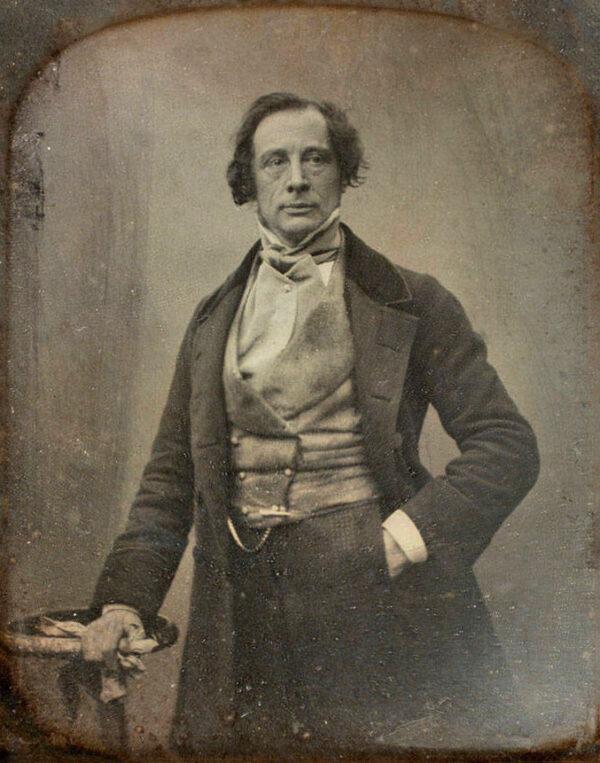

Will the real Dickens stand up? Daguerreotype portrait of Charles Dickens, 1852, by Antoine Claudet. Library Company of Philadelphia. Public Domain