“Don’t judge a book by its cover” is a popular adage that can be compellingly applied to many situations. However, its wisdom misses the mark in the context of treasure bindings.

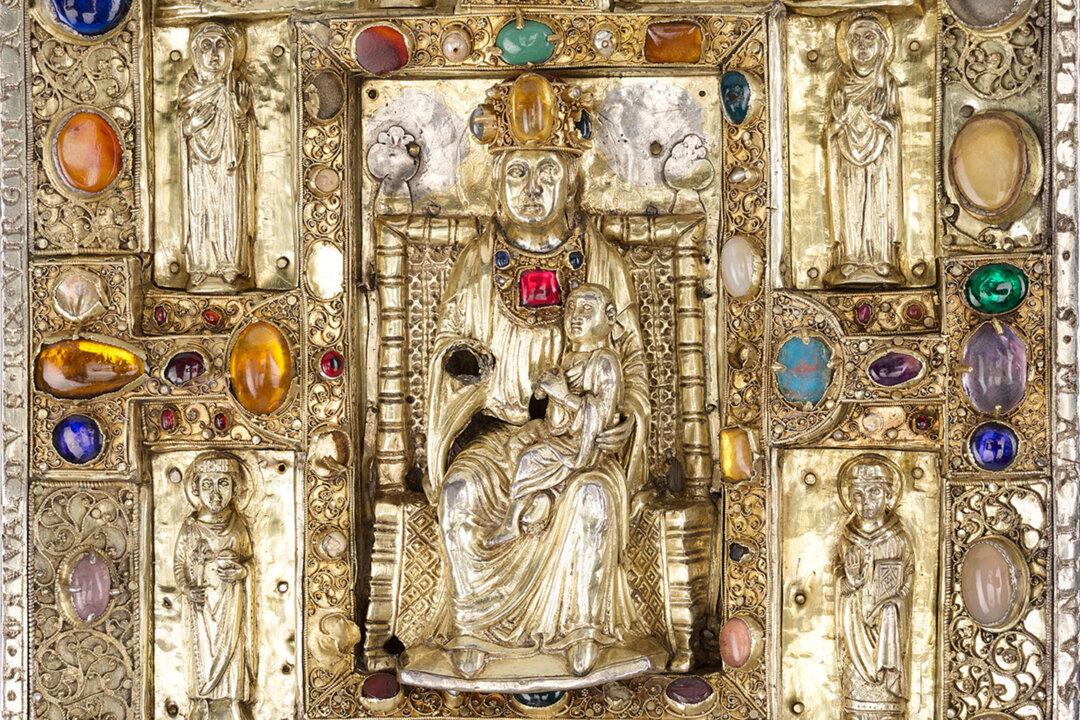

Treasure bindings, also known as jeweled bindings, are a type of bookbinding where covers are adorned with lavish materials which can include gems, silver, gold, ivory, and enamel. This style emerged during the Middle Ages and typically heralded that the book’s interior contained important and precious text along with beautiful miniature illustrations. Thus, the exterior adornment was appropriate veneration. These books were meant to be displayed not by their spines, but by their covers.