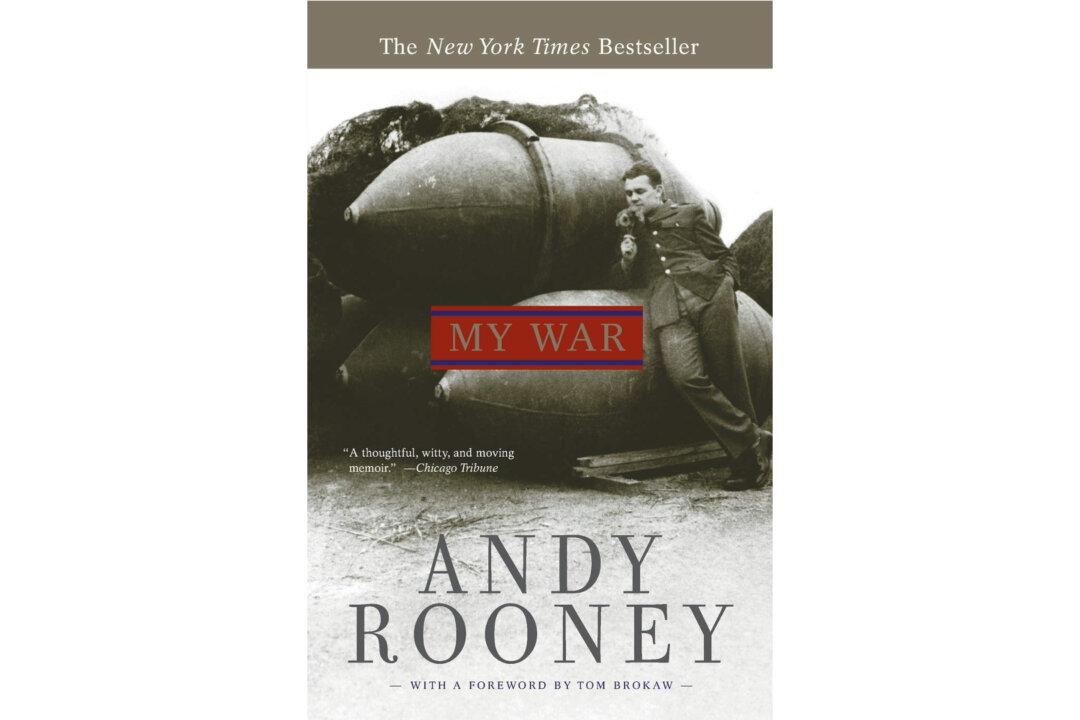

“My War” is part autobiography and part history book. Like any true journalist, author Andy Rooney writes about what he observed and experienced—truly capturing World War II’s minutia.

The college student and aspiring writer was drafted into the U.S. Army in August 1941 and began his journalism career with Stars and Stripes the following year. His job was to witness the war and write about it. He did so with flourish, writing in such a way that he took readers to the places he saw and survived. His style, in fact, fit what 19th-century essayist and poet Henry David Thoreau called a “sense of place.”