NEW YORK—The face of the first president of the United States is well imprinted on our minds. We see it countless times on the one-dollar bill. We take it for granted that this iconic image of George Washington and the portrait by Gilbert Stuart from which it was derived is what he really looked like. Yet, a more accurate likeness of Washington was sculpted by the Italian artist Antonio Canova.

This most celebrated neoclassical sculptor was born in 1757 to a humble family in the small town of Possagno, on the Venetian mainland. At the age of 23, he moved to Rome where he created sculptures and monuments for popes, emperors, kings, and aristocrats.

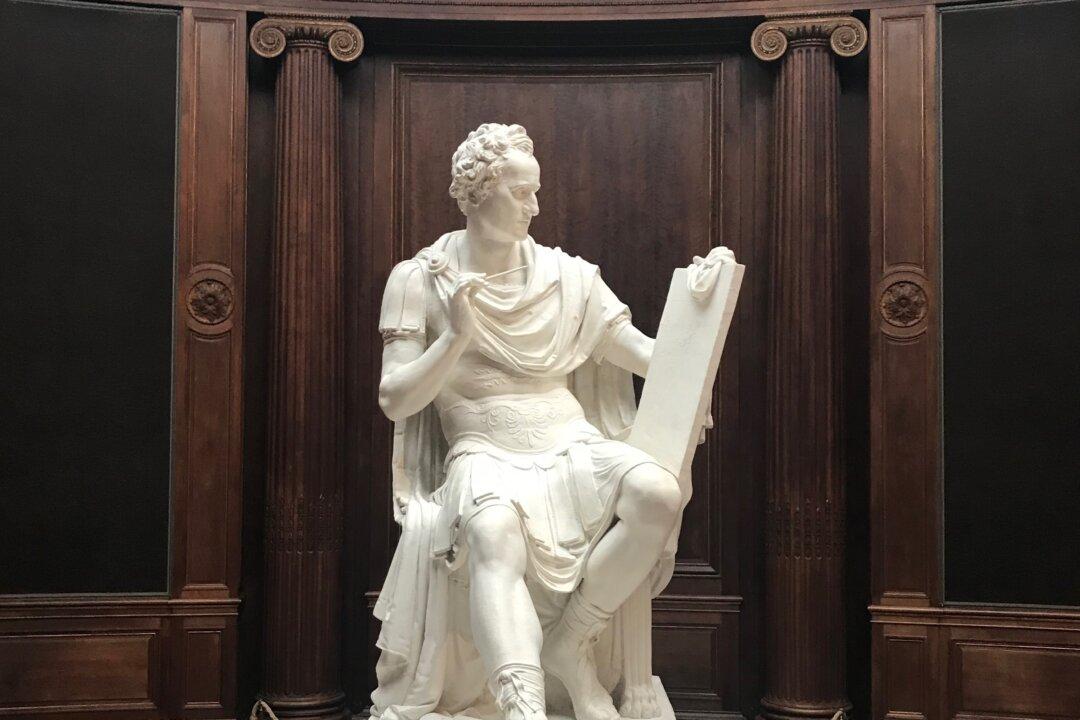

In 1816, Canova was commissioned by the General Assembly of North Carolina to create a marble statue of Washington to stand in the State Capitol in Raleigh. At that time, his sculptures were standing in Italy, France, England, Austria, Germany, Holland, Poland, and Russia.