Masks made by First Nations people continue to fascinate us.

Some who visit powwows or museums, such as the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Gatineau, Quebec, and the Vancouver Art Gallery, seem to admire aboriginal masks purely for their artistry and fine craftsmanship, while others are intrigued by the exotic and sometimes grotesque nature of the carvings. Yet others see a scholarly and psychological reason for people to make and use masks.

From an artistic standpoint, masks offer the greatest sculptural variety of Northwest Coast art. In fact, masks are among the most popular items in the vast collection of artifacts at the Canadian Museum of Civilization.

Masks from the Iroquois False Face Society and those done in the Northwest Coast style continue to be made by highly skilled artists. In fact, one such mask, a Tsonokwa Mask carved in 2007 by Beau Dick who lives and works in Alert Bay, B.C., was a highlight of Sakahan, the highly successful exhibit at the National Gallery of Canada this past summer.

Whether depicting human or animal figures, the masks give a glimpse of the supernatural world, which was mirrored by First Nations people when they wore them at their ceremonies. The painting on many of the Northwest Coast masks and their themes, ranging from detailed realism to supernatural monsters, has been compared favourably with the great art of ancient Egypt and China.

There are three main categories of masks: Clan Masks worn at feasts and potlatches; Secret Society Masks worn only at the time of the winter initiation dances; and Shaman Masks, belonging to the men and women who functioned as mediators between the people and the spirit world. Each shaman carved his or her own set of masks and the meanings were known only to the carver. The masks were buried with him.

Wood used include red or yellow cedar, spruce, hemlock, maple, and alder. Most masks were worn over the face, but some were made to be worn on the forehead. After metal tools were introduced by the fur traders, carvers were able to work at greater speed and produce more pieces, although the style remained basically unchanged.

In the post-contact period, commercial paints replaced the old natural dyes and pigments, but the traditional colour selection remained the same. Dyes were obtained by crushing red ochre, charcoal, clam shells, and copper oxide, and mixing them with an oily base of salmon roe or other fish eggs squeezed through a cedar bark sack.

One very special Tsimshian mask on display at the Museum of Civilization is a stone mask known as the “blind” mask. Its twin, the “sighted” mask, resides at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. The twin masks, which are the only known stone masks in existence, were separated over 100 years ago.

The blind mask fits under the twin, and it is believed that the dancer wearing the mask could deftly cover it with the sighted mask, making his audience believe that the being could open and close its eyes.

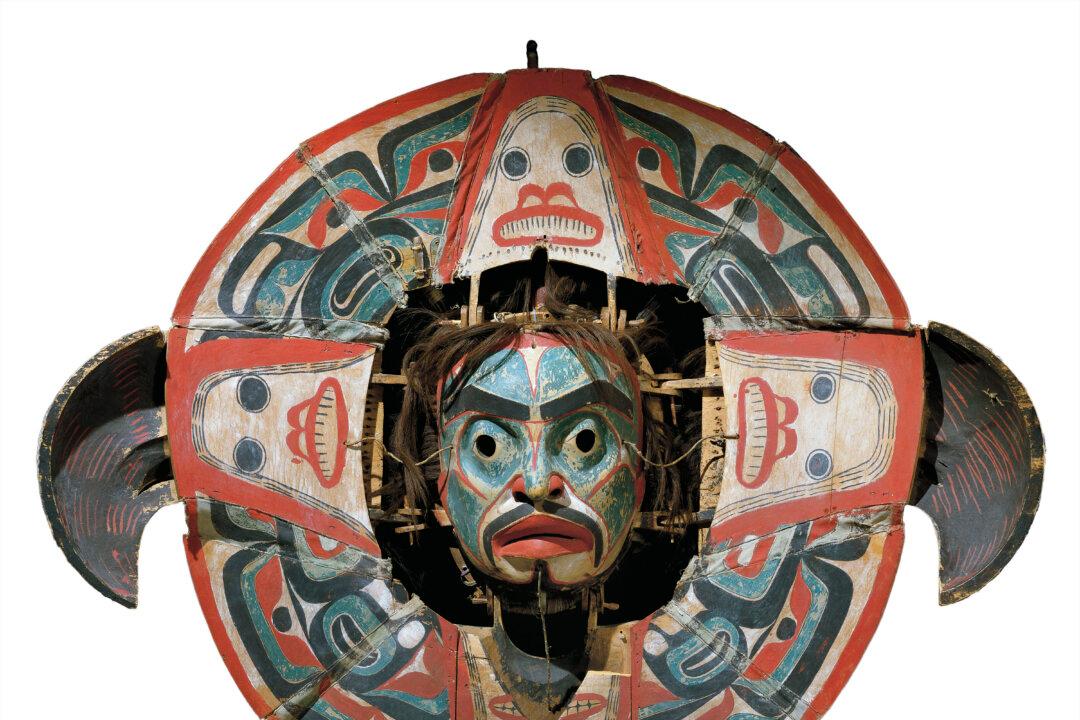

Another exceptional mask—one of Canada’s greatest national treasures—is a Haida Heiltsuk transformation mask. By pulling various strings, the mask can be transformed from its outer image of an eagle to the inner one of a supernatural being in human form.

To see these rare treasures, visit the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Gatineau, Quebec, or visit: www.civilization.ca

Susan Hallett is an award-winning writer and editor who has written for The Beaver, The Globe & Mail, Wine Tidings, and Doctor’s Review among many others. Email: [email protected]

Canada’s Northwest Coast Mask Art

Some who visit powwows or museums, such as the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Gatineau, Quebec, and the Vancouver Art Gallery, seem to admire aboriginal masks purely for their artistry and fine craftsmanship, while others are intrigued by the exotic and sometimes grotesque nature of the carvings. Yet others see a scholarly and psychological reason for people to make and use masks.

A Heiltsuk Transformation Mask. By pulling various strings, the mask can be transformed from its outer image of an eagle to the inner one of a supernatural being in human form. Photo courtesy CMC/MCC

|Updated: