NR | 1h 43m | Documentary, Biography, Film History | 2016

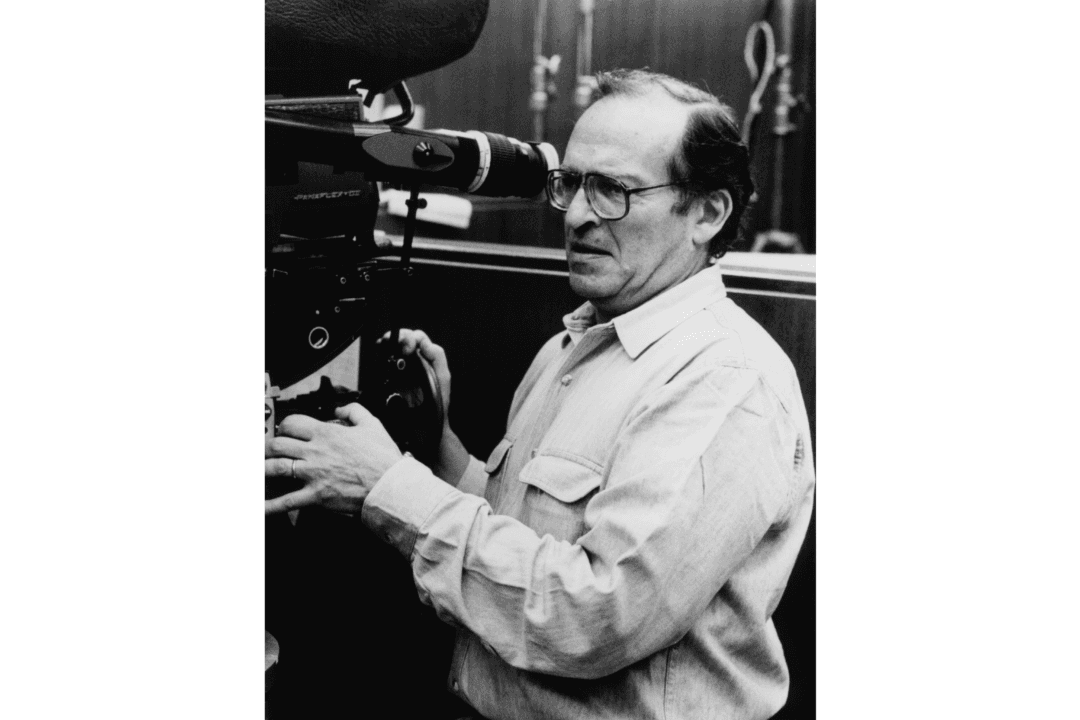

One of the very few directors to enjoy success during Hollywood’s Golden Age, the American New Wave, and way beyond, Sidney Lumet never followed any trends or adhered to anything resembling formula. Far from a household name at any point in his career, Lumet shunned the spotlight and instead let his work speak for itself.