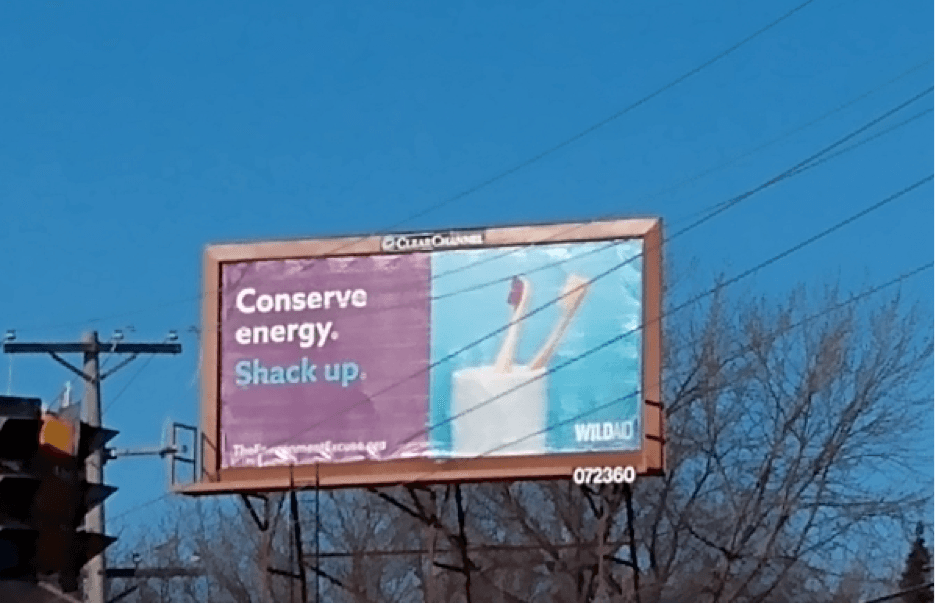

Roadside billboards are intentionally eye-catching, seeking to gain the one or two seconds of attention a driver has as he zips by on his way to work or an errand. I’ve seen some pretty shocking billboards over the years, but the one I saw while driving the other day reached a whole new level.

This billboard wasn’t shocking for the image it contained—two toothbrushes sitting in a cup. Instead, it was shocking because of its—pardon the oxymoron, but it’s the best way I can think to describe it—subtle overtness. “Conserve energy,” it said, and then, “Shack up.”