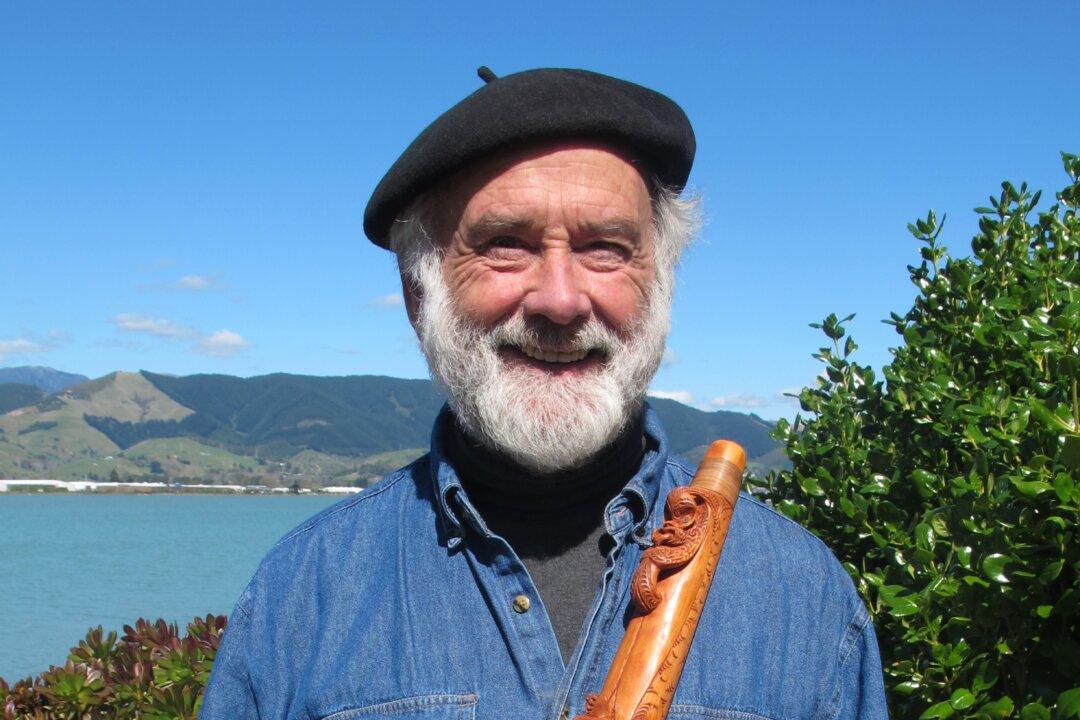

Until some 40 years ago, traditional Maori music was thought to be all but lost. Then Brian Flintoff, along with a band of other enthusiasts, began a revival of Maori flute and instrument making and playing.

Now a world-renowned master carver, Flintoff overflows with enthusiasm for the traditional Maori musical instruments he makes. Flintoff’s instruments are in private and museum collections around the world, including the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix, Arizona.