Most of us have no memory of when we first heard it. A simple melodic phrase moves stepwise between adjacent notes on the scale, without dissonance or unexpected tension. The gentle rhythm of the 6/8 time emulates a rocking cradle, creating a feeling of warmth and security. A subtle shift in the slow, balanced harmony prevents tedium. Nevertheless, by the second time it is repeated, you begin to nod off. By the end, sleep overtakes you.

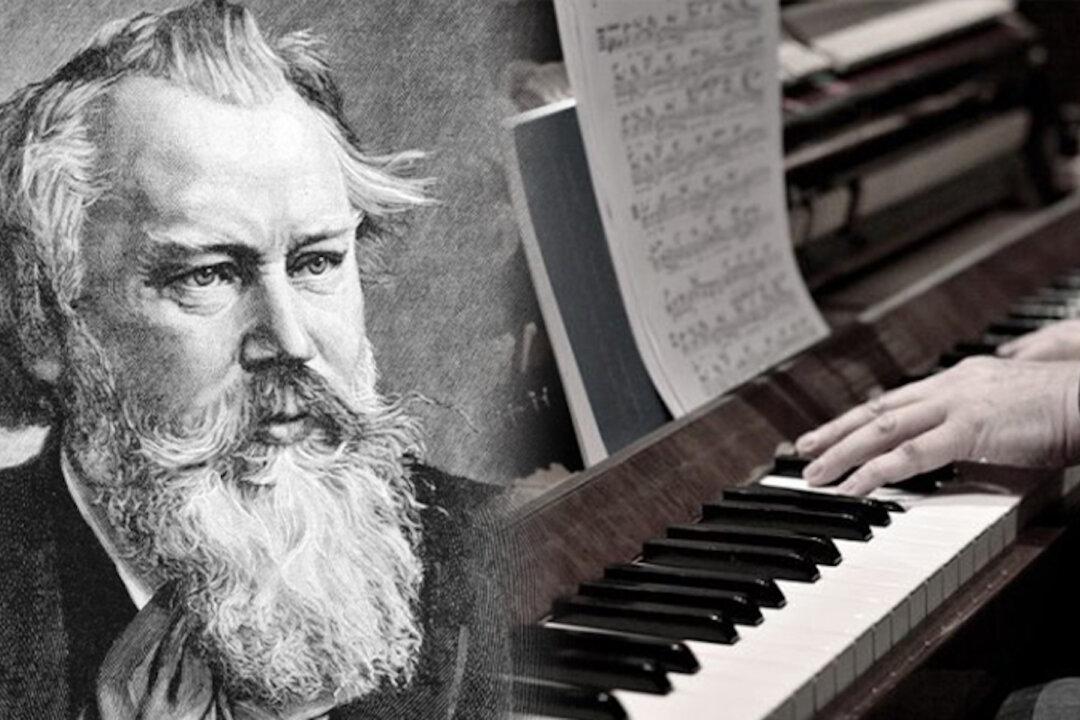

The song is the “Wiegenlied,” or “Cradle Song.” Also known as “Brahms’s Lullaby” (Op. 49, No. 4), it is one of the world’s most universally recognized tunes. The story of how Johannes Brahms came to write it is as interesting as the piece itself.