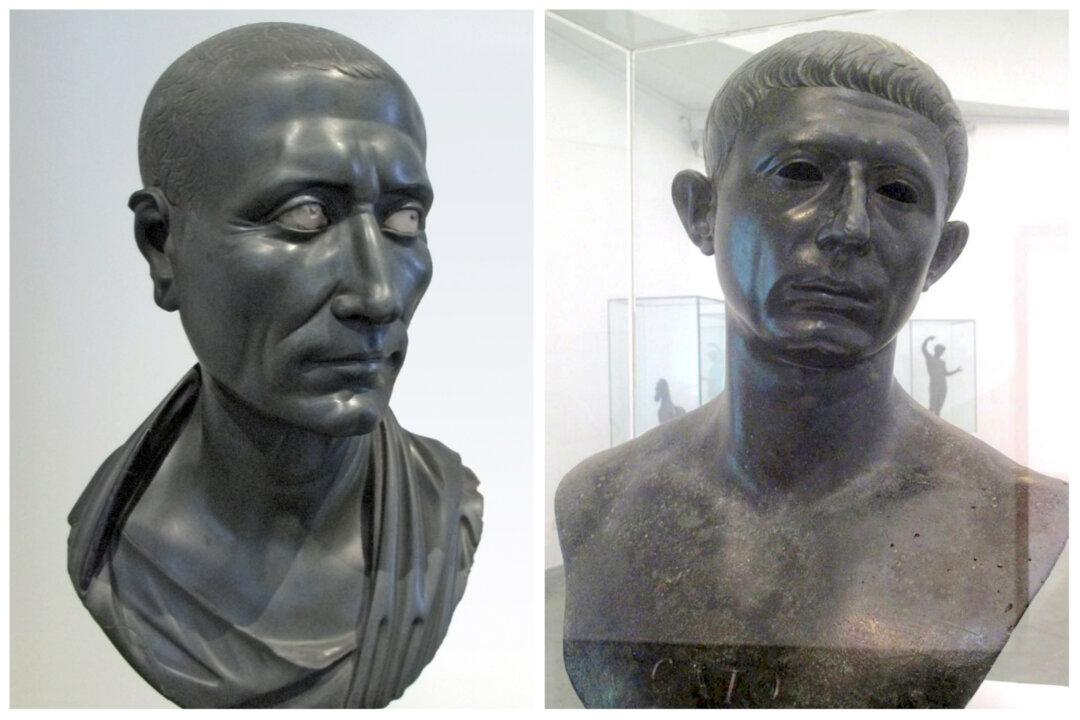

For those interested in the history of statecraft, there are few topics more compelling than the Roman Republic, and in particular the reasons for its fall. Josiah Osgood, professor of classics at Georgetown University, has written an insightful and important work on this topic.

His book “Uncommon Wrath: How Caesar and Cato’s Deadly Rivalry Destroyed the Roman Republic” delves into the political warfare waged between two of Rome’s leading men of the first century B.C.—Julius Caesar and Cato the Younger.