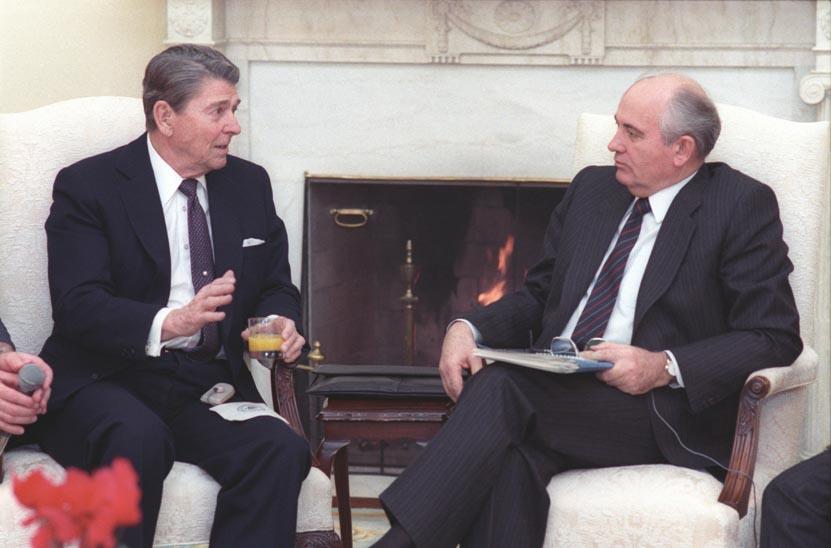

On May 31, 1988, President Ronald Reagan stood on Soviet soil and addressed a packed audience at Moscow State University. This fourth in a series of summits between Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev was part of their tireless efforts to reduce the nuclear threat at the time. Reagan understood that this wasn’t a ceremonial visit. Although the world leaders had personal chemistry, Reagan and Gorbachev were combatants, and the winner would determine the future of civilization.

How did Reagan get to this point? Bret Baier (the chief political anchor for Fox News), with Catherine Whitney, traces Reagan’s journey in the book “Three Days in Moscow: Ronald Reagan and the Fall of the Soviet Empire.” It is basically a biography of Ronald Reagan, with emphasis on his interaction with Mikhail Gorbachev to end the Cold War.