Many of us have shied away from the world of ancient Greek tragedies, thanks to inadequate but mandatory high school classes on the topic. Yet Bryan Doerries, in his new book “The Theater of War,” is determined to break the stigma associated with classical tragedies in order to show readers that these works of the ancient Greeks are just as relevant as ever.

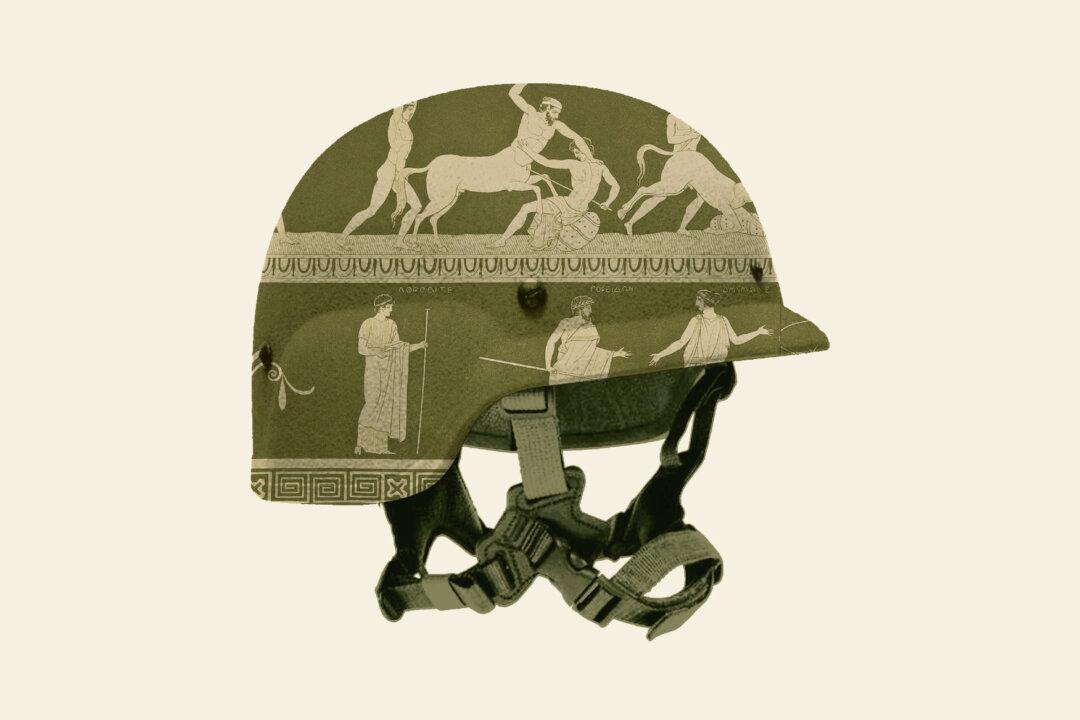

The passionate nature of Greek tragedy is given new life as Doerries embarks on a mission to bring these stories of loss to the ones who seem to have lost it all—soldiers, prisoners, and hospital patients.

It all began with a kairos, an ancient Greek word that Doerries defines as “the right moment, the moment that should be seized, or that seizes you.” In his own kairos, Doerries was reading Euripides’s “Medea” and began visualizing a group of imaginary actors performing the piece the way that Doerries would have it done.