With all the chaos of screaming heads running frantically along the political aisles of capitols, universities, main streets, and neighborhoods, there’s confusion as to why, exactly, we are screaming and running. Our modern American society has acclimated itself to finger-pointing, as if that action has ever produced clarity.

Many problems are at the root of this chaotic discourse, and Glenn Ellmers, the Salvatori research fellow on the American Founding at the Claremont Institute, appears to have pinpointed one of the primary sources: our political philosophy (or lack thereof).

The Polar Opposites

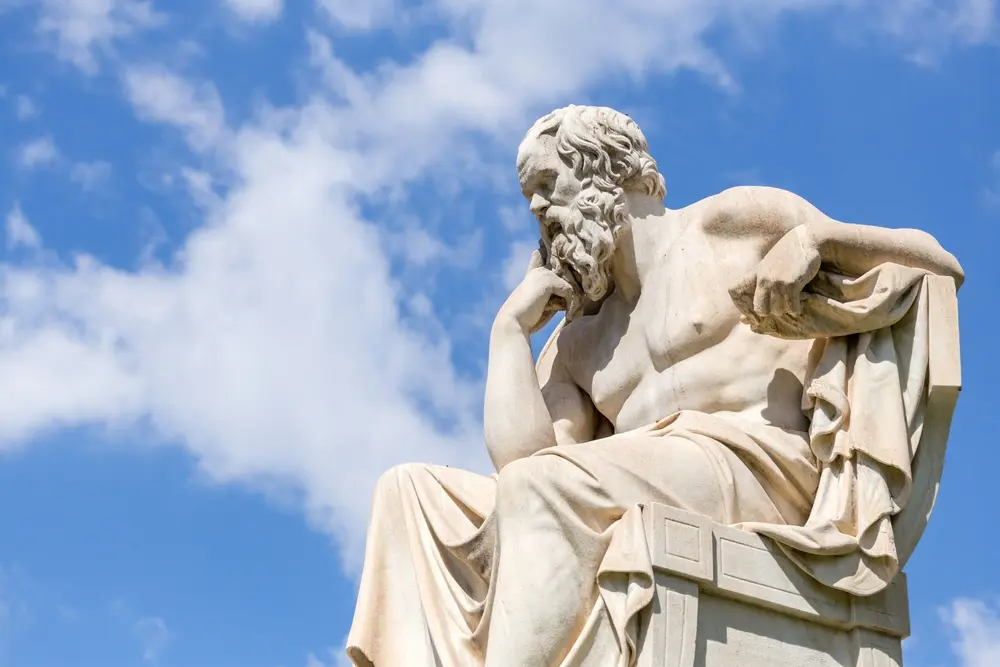

Ellmers dives into this Western issue in his new work, “The Narrow Passage: Plato, Foucault, and the Possibility of Political Philosophy.” The two names in the title are indicative of not just the book but the current philosophies held in the West and America primarily. Plato and Michel Foucault are not only separated by millennia, but their philosophical differences are on equally opposite ends of the philosophical spectrum.