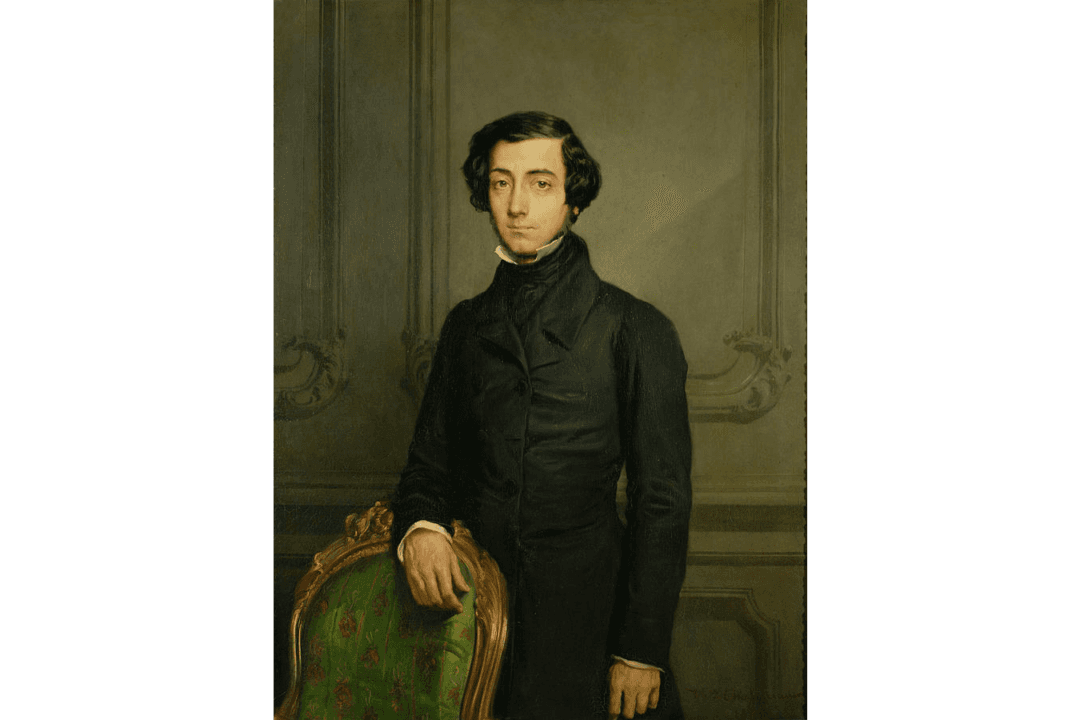

Arguably the preeminent scholar on Alexis de Tocqueville has written a new biography on the French aristocrat who defied aristocracy in favor of democracy. Olivier Zunz, the James Madison Professor of History at the University of Virginia, has assembled a studious work on the life of an incredibly studious man.

“The Man Who Understood Democracy: The Life of Alexis de Tocqueville” is a wonderfully written biography on the foreigner who arguably best described America politically and socially through his work “Democracy in America.”