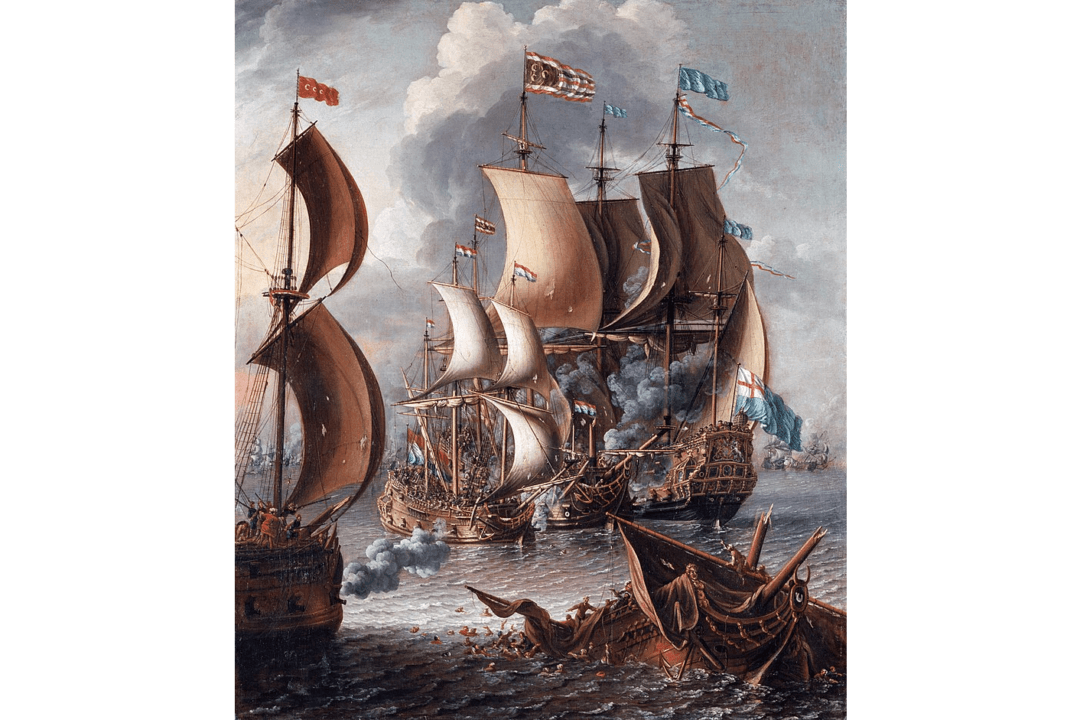

There are hidden gems among the treasures of history, and when historians and writers stumble across them, it is a true gift when they share them with the rest of us. Des Ekin, historian and journalist, has found such a gem in James Leander Cathcart among the treasures of American history. In his new book, “The Lionkeeper of Algiers: How an American Captive Rose to Power in Barbary and Saved His Homeland From War,” he has shared it with the rest of us, and we can only be so grateful.

I rarely start a review in such an immediately complimentary capacity, but I found myself so absorbed in this book that I find it difficult to start any other way.