My grandfather on my mother’s side was a self-taught lawyer. His jurisprudence was practiced in Socorro, New Mexico, in the late 1800s. Some of my relatives say that he lobbied for statehood, though that effort didn’t succeed in New Mexico until 1912.

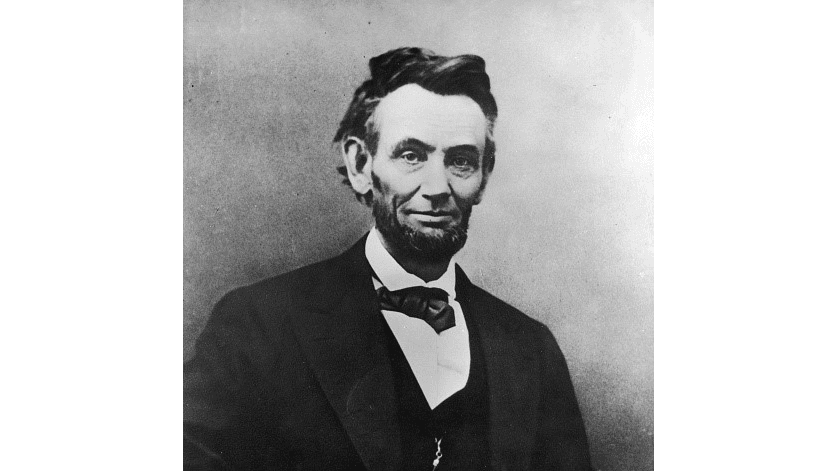

It was more than 50 years earlier, in 1860, that another self-taught lawyer was lobbying his case against a field of 11 at the Republican National Convention held in the bustling city of Chicago. A little-known Illinois country attorney, Abraham Lincoln, was seeking the Republican nomination for president.