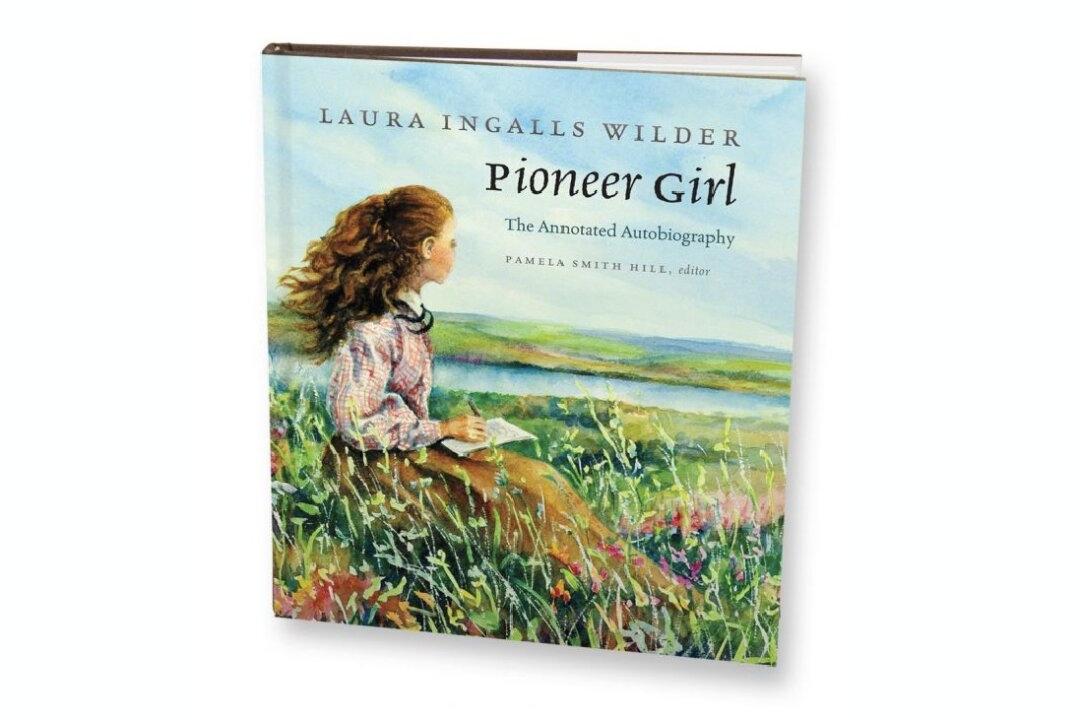

Laura Ingalls Wilder is one of the most recognized names of children’s literature—and for good reason. It was she who brought tales of America’s pioneer days to thousands of young readers and introduced them to the genre of historical fiction. In fact, fiction is truly where those beloved “Little House” books belong. Although Wilder passed away in 1957, her dedicated fans can enjoy a new, “truer” account of her life in “Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography,” complete with carefully researched editorial embellishments.

In 1930, a retired and restless Wilder sat down to write about her life as one of the many hopeful souls in search of a prosperous future. She wrote this first draft—titled “Pioneer Girl”—as an autobiography, but the project was abandoned in favor of the fictionalized book series for children.

Wilder never saw “Pioneer Girl” published, but as of late 2014, her followers can read her story as it was originally intended. “Pioneer Girl” is essentially the seed of the “Little House” series as we know it. As such, fans of her books will recognize many of the stories, places, and characters.