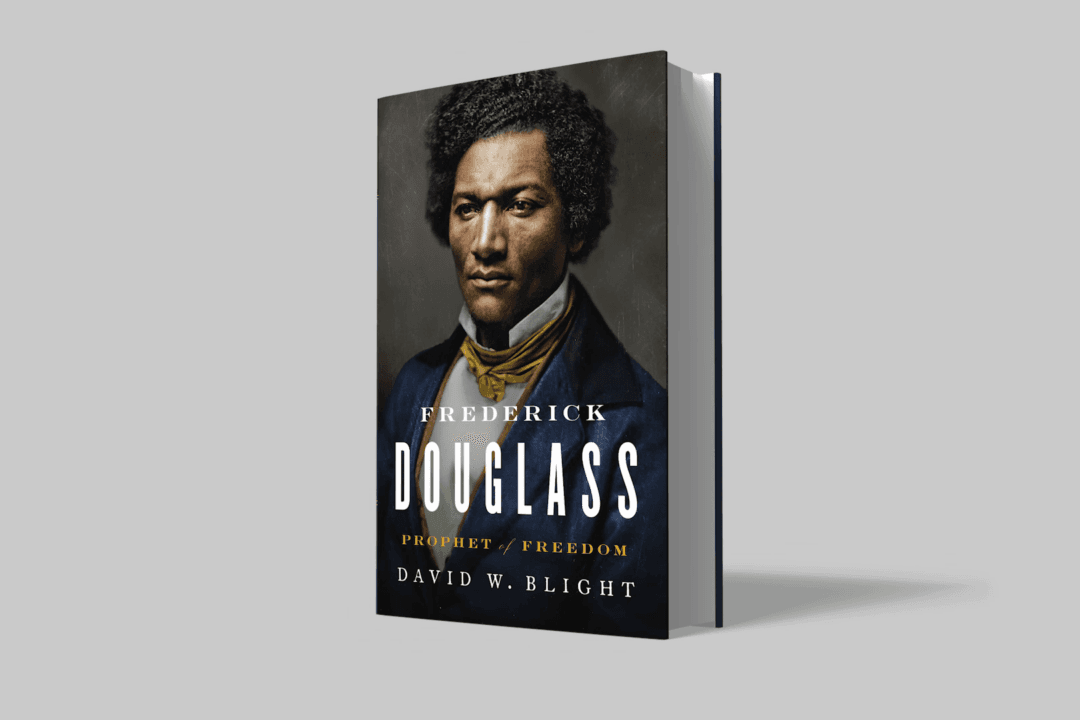

An extraordinary biography, “Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom” by David W. Blight seems to have captured Douglass’s mind and heart as well as another human being can. And, like his subject, Blight has a real gift for the written word. This book truly inspires by attesting to the fact that one person, no matter how humble his or her beginnings, can change the world.

Blight states that he would not have written Douglass’s biography if he had not encountered the private collection owned by Walter O. Evans of Savannah, Georgia. Evans’s collection, as well as recently discovered issues of Douglass’s newspaper, provided new insights for Blight into the final third of Douglass’s life. Because of this archived material, Blight believes he has written the fullest account of Douglass’s life.