“I am an uneasy man, severe with myself, like all solitaries.” — Blaise Cendrars

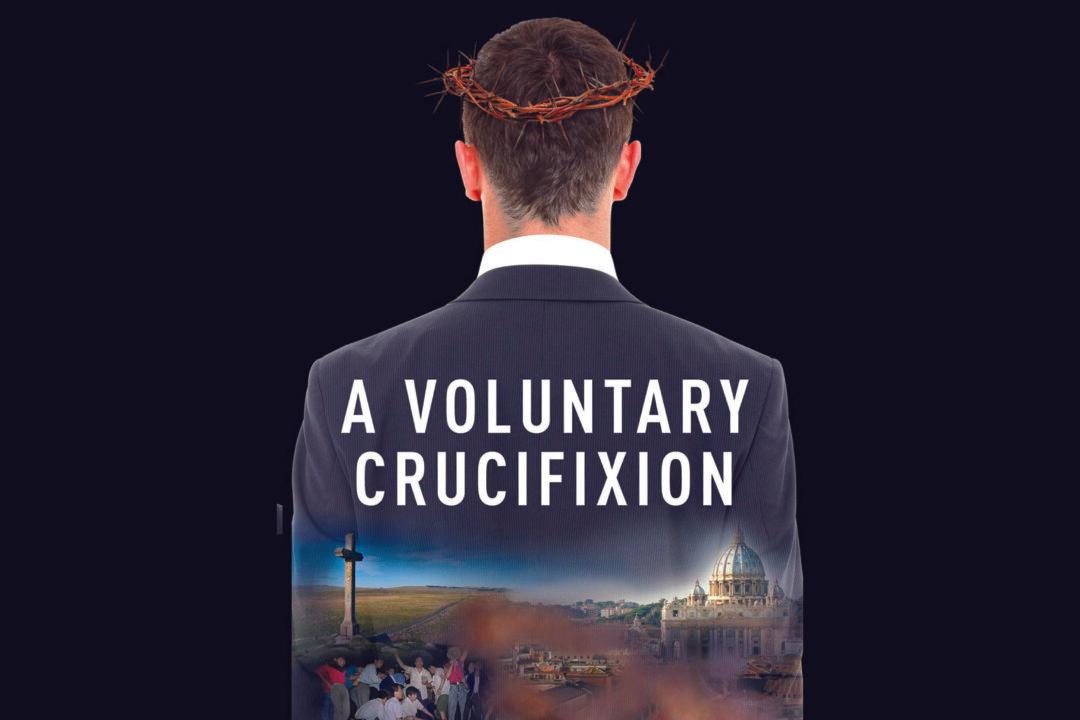

David J. MacKinnon’s “A Voluntary Crucifixion” is a book about memory and the elusive task of capturing in prose the people, places, and events that have gone into making an eventful life.