NEW YORK—Carl Weisbrod was two years out of graduate school, planning a career in law, when a new book about municipal builder Robert Moses changed his life: Robert Caro’s “The Power Broker.”

“It had a profound effect on me,” says Weisbrod, now the chair of New York City’s planning commission. “It really got to me to see that planning and development was as important as human services in terms of how it shaped people’s lives.”

A generation of city planners and builders have come of age since Caro’s 1,300-page, Pulitzer Prize-winning biography was published 40 years ago. Celebrated for its exhaustive detail, controversial for its startling disclosures, Caro’s book has been cited as inspiration for a new approach to urban planning — more modest in scale, more focused on community involvement.

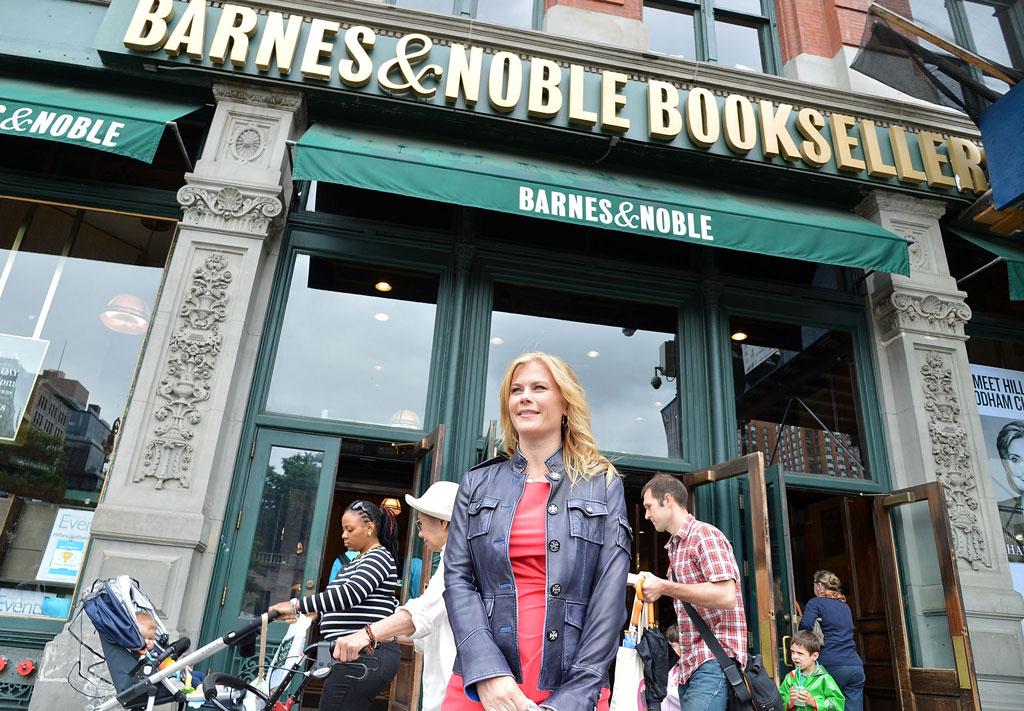

The book remains widely read and talked about, and in the opinion of many, stands as a modern classic. “The Power Broker,” ranked No. 92 on the Modern Library’s list of the greatest nonfiction works of the 20th century, continues to sell 10,000 copies a year, according to publisher Alfred A. Knopf; and is a standard text for sociology, city planning and urban history courses.

“When I was teaching, I always assigned it,” says Eloise Hirsh, a former teacher at Carnegie Mellon University and a former planning director in Pittsburgh who now administers a New York City park. “That book is so much about what you have to do in government to make things happen.”

“Students would blanch at the beginning, because of how thick the book was, but once they got into it, it read like a novel,” says Weisbrod, who used the book while teaching at Columbia University and New York University.

New York City was nearly bankrupt when “The Power Broker” was released, and Moses, who died in 1981, was out of office and out of favor after an extraordinary four-decade reign that saw him outmatch mayors, governors and even presidents and implement much of the city’s infrastructure in the 20th century. A human monument of vision, energy and ruthlessness, he built hundreds of playgrounds, hundreds of miles of roadways and 13 bridges.

At one point, he held a dozen appointive state and city positions. Early in his career, he was praised as a dynamic reformer who restored and revitalized New York’s parks during the Great Depression and masterminded such landmark public works projects as Jones Beach. But by the late 1960s, he was widely condemned as heartless and corrupted, tearing down neighborhoods and disdaining mass transit in favor of automobiles.

Caro sees “The Power Broker” as not only a biography, but a history of New York City and a primer on politics. During a recent interview with The Associated Press, the 78-year-old author explained that he first thought of the book in the 1960s when he was an investigative reporter for Newsday and realized that Moses, an unelected official, could essentially implement his ideas at will.

“You’re seeing the raw, naked realities of power, as opposed to the textbook version of power that we learned in high school and college,” says Caro, who has spent the decades following “The Power Broker” writing a multivolume series on Lyndon Johnson. Noting its ongoing presence in classrooms, Caro said “The Power Broker” has succeeded as he had hoped: “teaching kids about power.”

Setting a pattern that has continued with the Johnson books, he had intended to write “The Power Broker” in nine months, but ended up needing several years. Caro turned in a manuscript of more than 1 million words that was eventually cut to around 700,000, still well over 1,000 pages.

Despite complaints that Caro was too harsh on Moses, his book remains so definitive that its legacy is inseparable from the legacy of Moses. Defenders of Moses have said that his excesses should not cancel out his achievements, but Caro himself cautioned against overreaction. In the book’s introduction, he noted that before and after Moses’ 40-year reign, few major projects were launched and completed in New York City.

“Robert Moses may have bent the democratic processes of the city to his own ends,” he wrote, but a better way to construct public works in an urban community is one “which democracy has not yet solved.”

Con Howe, the former director of planning for Los Angeles, sees the book as an illustration of unchecked power, but also of achievement. He spoke of a current project in Los Angeles, where efforts to expand a subway line have been delayed because Beverly Hills residents want tunnels that were supposed to run under Beverly Hills High School to be redirected, with a fear of terrorism among the concerns raised.

“Some of the questions raised by ‘The Power Broker’ are still absolutely relevant,” Howe says. “It’s funny. I‘ll be with all my right-thinking, liberal, public do-gooder friends. And someone will say, ’We’ve got to get this subway system built and figure out how to prevent all these delays.‘ And I’ll say, ‘Guess who else would have used those words?’”