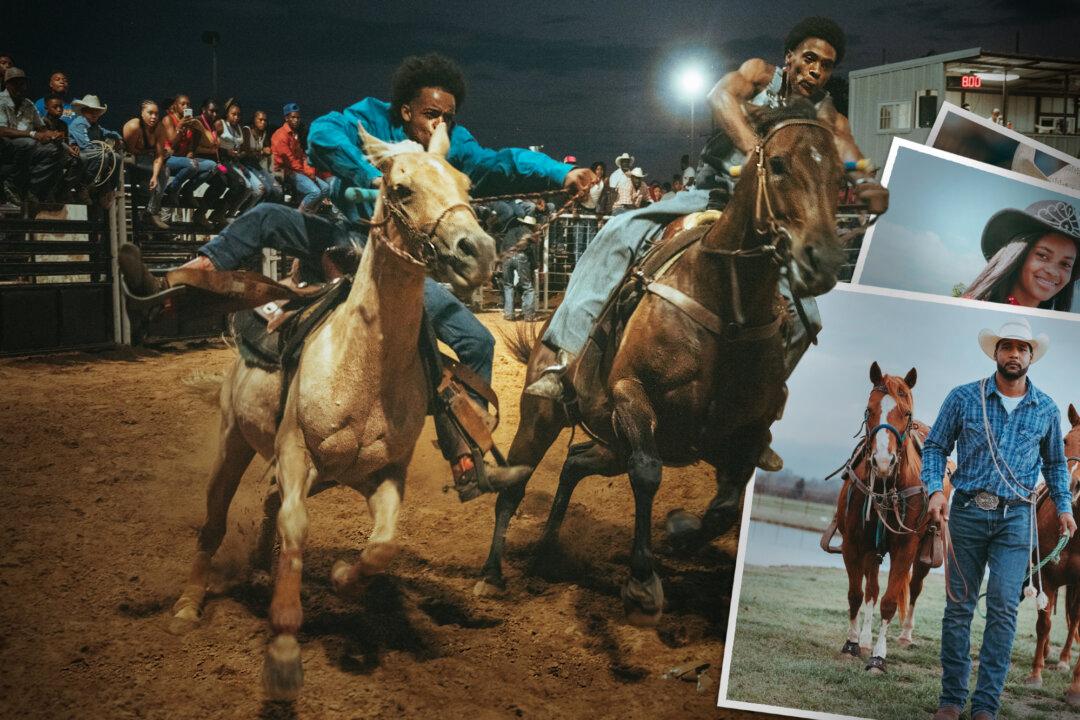

Colorful vibes jumped out at Ivan McClellan when he attended a black rodeo for the first time—everything popped, from the funky beats to the vibrant clothes to the cheers of the crowd. Even the rodeo clowns sparkled.

When a filmmaker first asked McClellan, 42, to photograph a black rodeo, he thought it sounded crazy. Who knew black rodeos even existed? But the filmmaker, who was making a documentary on black rodeos, assured him it was no joke.