In the small Quaker town of Springfield, Pennsylvania, John West and Sarah Pearson welcomed Benjamin West (1738–1820) into the world. He was the 10th and last of John’s children from two marriages. The son of an innkeeper growing up away from city life, West was not exposed to art, yet he possessed a passion for drawing. When he was 6, he drew a picture of his sleeping niece in a cradle. According to John Galt, West’s biographer: “He looked at it [his niece] with a pleasure which he had never before experienced, and observing some paper on a table, together with pens and red and black ink, he seized them with agitation, and endeavored to delineate a portrait.”

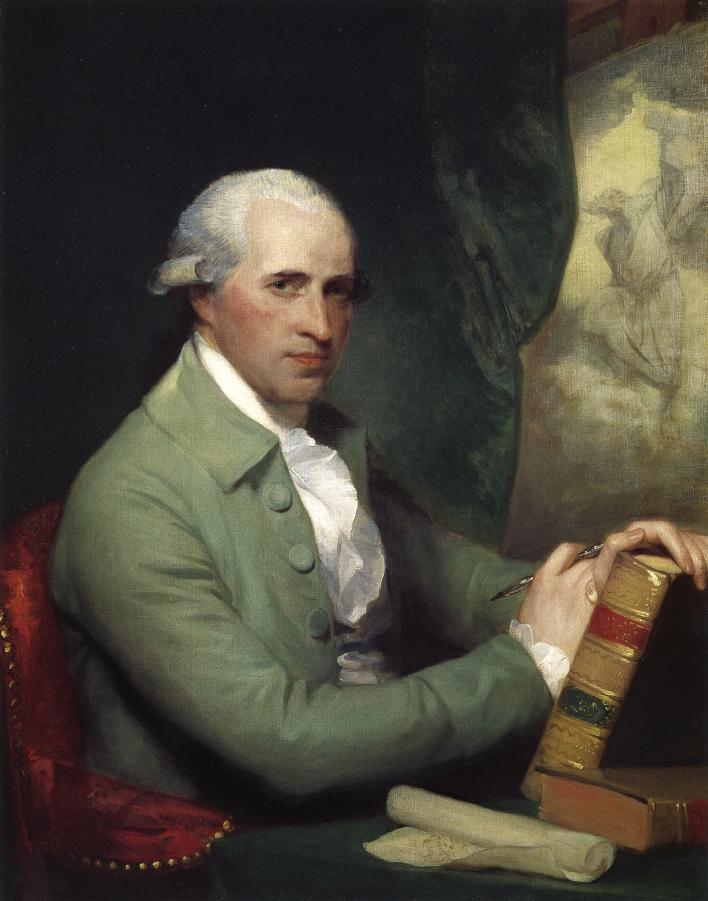

A portrait of Benjamin West, 1781, by Gilbert Stuart. The National Portrait Gallery, London. Public Domain