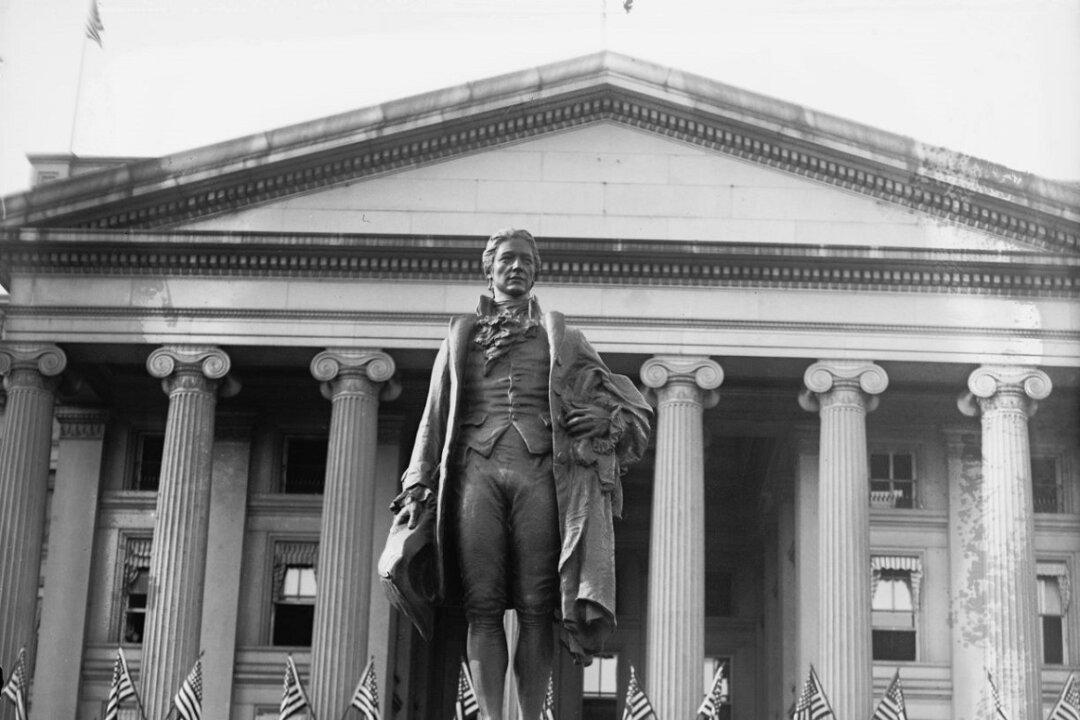

Noble statues “enrich the city in beauty, in meaning, and in purpose,” author Michael Curtis wrote in his book “Classical Architecture and Monuments of Washington, D.C.: A History & Guide.”

Curtis reminds readers that sculptures are different from statues: Sculptures “might contain any idea large, small or insipid of anything or non-thing or nonsense,” he wrote. “Statues are intelligently composed, aesthetically resolved, expertly crafted tributes to civic, military, and humanitarian accomplishments.”