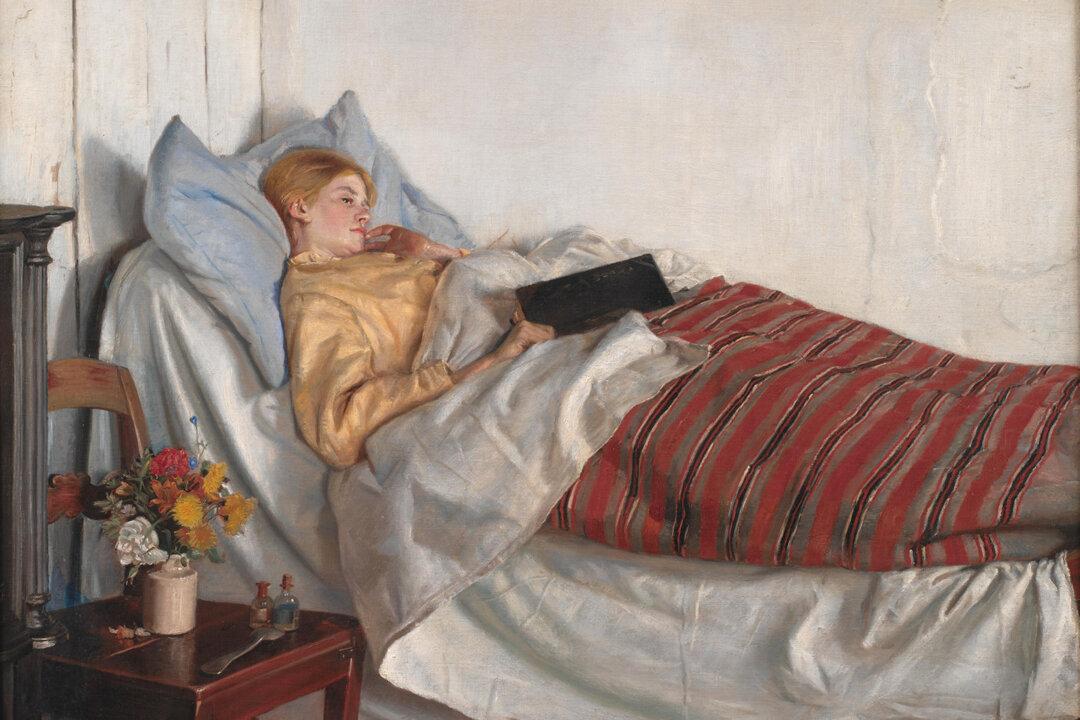

Most of us were created in one, many were born in one, and many have died in one. Most of us spend a third of our lifetime in one, where we read, converse, make love, sip a glass of evening wine or a cup of morning coffee. It is a hospice of health and restoration, a refuge where the anguished can weep alone, a protective castle to which small children flee in the middle of the night to escape the terrors and specters cloaked in the darkness. It is both bastion and battleground for husbands and wives. It is the vehicle that carries us from light, lucidity, and reason to a land of dreams and nightmares.

I refer, of course, to the bed.