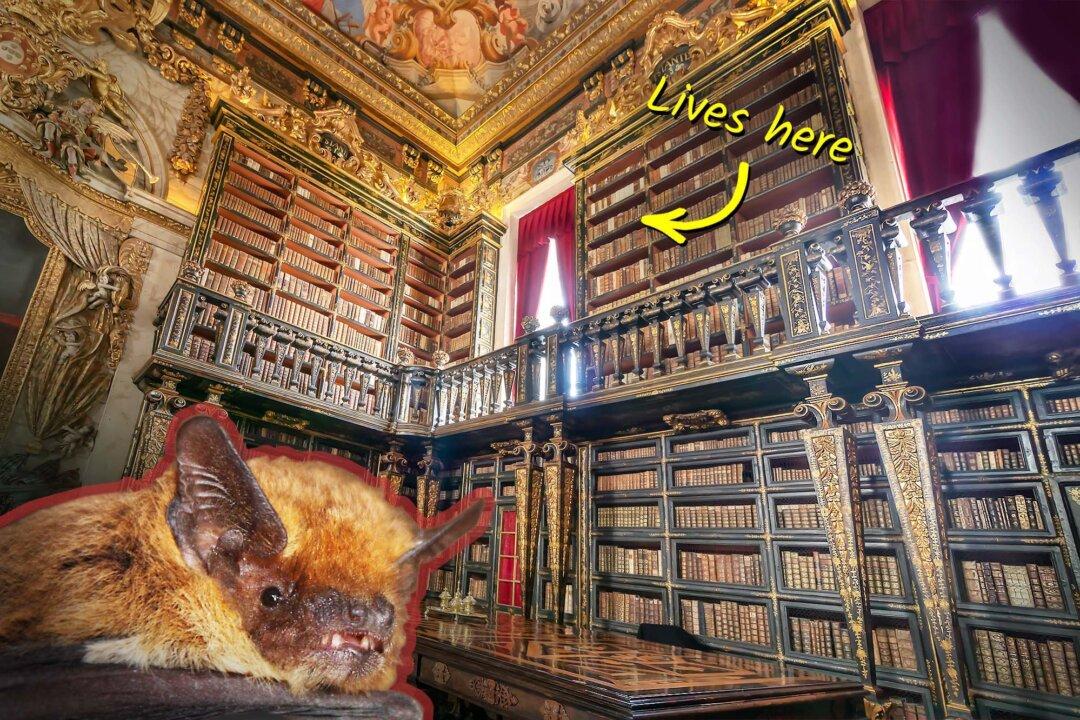

They fold their leathery wings by day, hanging by hook-like claws high in the rafters. They rest unseen behind grand gilded bookcases until dusk when they come out to feast.

They are bats in the library—waiting till dark to snatch up the bugs that else would feed upon the priceless books in keep.