NEW YORK—The more you learn about Leonardo da Vinci, you are left with less of the man and more of the legend.

Though Leonardo is best known as a Renaissance painter, he actually didn’t create that many paintings, and the 15 or so that have been credited to him were not entirely his creation but the results of his collaboration with his students. He was a delegator, a daydreamer, and an endless tinkerer. He was brilliant, but procrastinated, and had trouble finishing what he started.

The original works he left behind are few in number. There are only 10 drawings by Leonardo in public American collections, according to Morgan Library associate curator Per Rumberg.

The Morgan, despite its huge drawings and prints collection, has only one that is on display now—a design for a device to scale towers during naval sieges.

Biblioteca Reale, Turin, has 13, most of which will make their home in a dimly lit gallery at the Morgan Library until February.

“In the next three and a half months, we will have doubled the number of Leonardo drawings in this country,” Rumberg said during the opening of the exhibit on Oct. 25.

Breaking a False Dichotomy

Today we tend to think of Leonardo as a man who bridged art and science. He is the archetype of the Renaissance man: an artist, engineer, mathematician, musician, architect. We marvel at the way he hopscotched between left-hemisphere and right-hemisphere thinking.

The exhibit is organized loosely into two parts: the front half of the gallery deals with his inventions and observations of the human body, the flight of birds, the anatomy of insects and musculature of horses. The back half includes drawings of figures and studies for paintings, both by Leonardo and his students.

But during the Renaissance, art and science were both born out of the study of nature. One could not understand perspective or depict living beings without a firm grasp of human perception and the natural world. Art and science were merely different means of discovering truth.

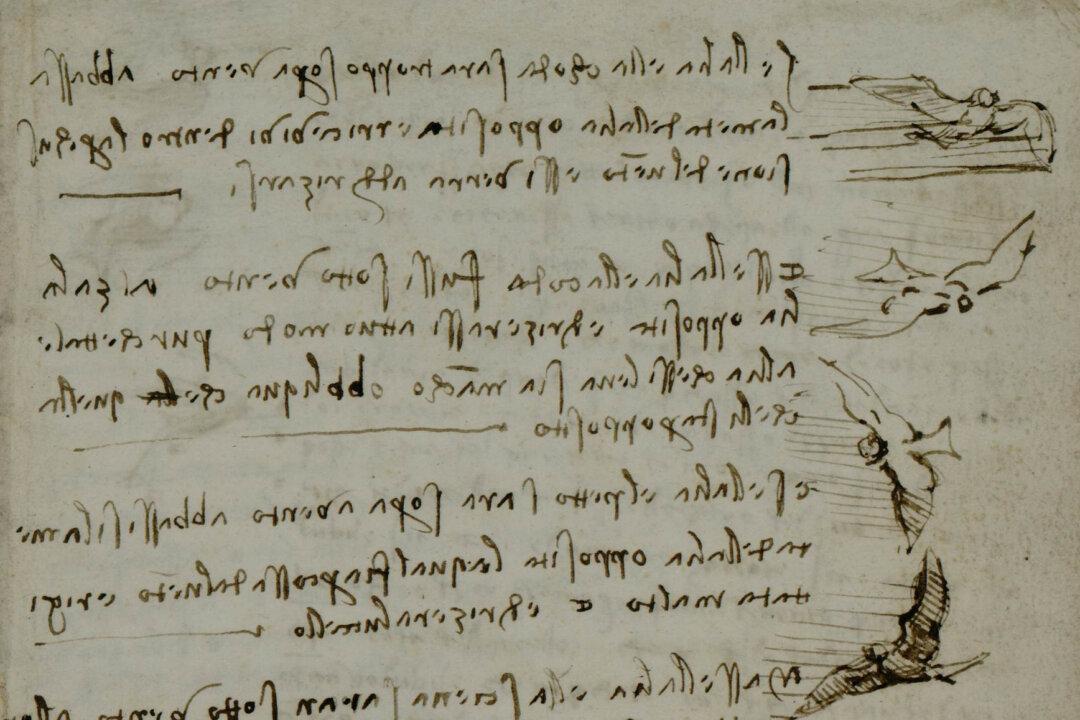

The highlight of the exhibit illustrates this idea perfectly. Leonardo’s 36-page sketchbook, the “Codex on the Flight of Birds,” was reconstituted from loose pages and is displayed in a glass case in the middle of the gallery. It’s a small, yellowed notebook covered in neat rows of mirror writing. (Leonardo wrote backwards unless he meant for others to read it.) In the margins, little seagulls or swallows illustrate the text, dipping and climbing in the wind.

“Leonardo was fascinated by the idea of flight, and here examines how birds manage to fly, keep their equilibrium, steer, rise, and descend,” Rumberg said. “Like most of his notebooks, it is a very mixed bag—there are architectural drawings, even a shopping list.”

The notebook is valuable and charming because it demonstrates the way he thinks.

This exhibit is named after Leonardo da Vinci, but it’s as much about his own work as that which he inspired—a large proportion of the drawings shown are by his students or followers.

Neither this exhibit nor any other could possibly satisfy our curiosity about such an illustrious man, but it should inspire us to probe big questions with as much intensity and determination as he did, and to record our thoughts and observations.

Leonardo da Vinci: Treasures from the Biblioteca Reale, Turin

Oct. 25–Feb. 2

Morgan Library & Museum

225 Madison Ave.

212-685-0008

themorgan.org; $12–$18