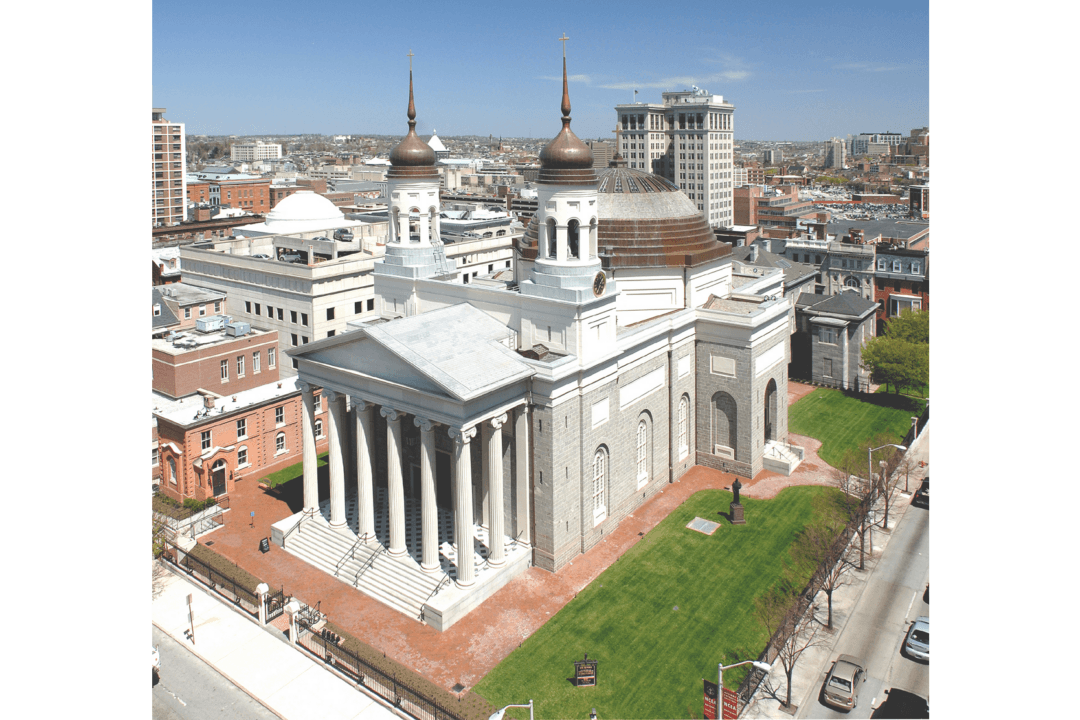

In 1806, John Carroll was America’s first Catholic bishop. His family was instrumental in the founding of the United States, and Carroll had the further satisfaction of seeing work commence on the new nation’s first cathedral. Now known as the Baltimore Basilica, the church is the greatest masterpiece of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, early America’s preeminent architect.

Best remembered for designing the original dome of the nation’s Capitol building, Latrobe was in high demand at a time of prolific construction. Carroll’s task for him, if far from simple, was at least straightforward.