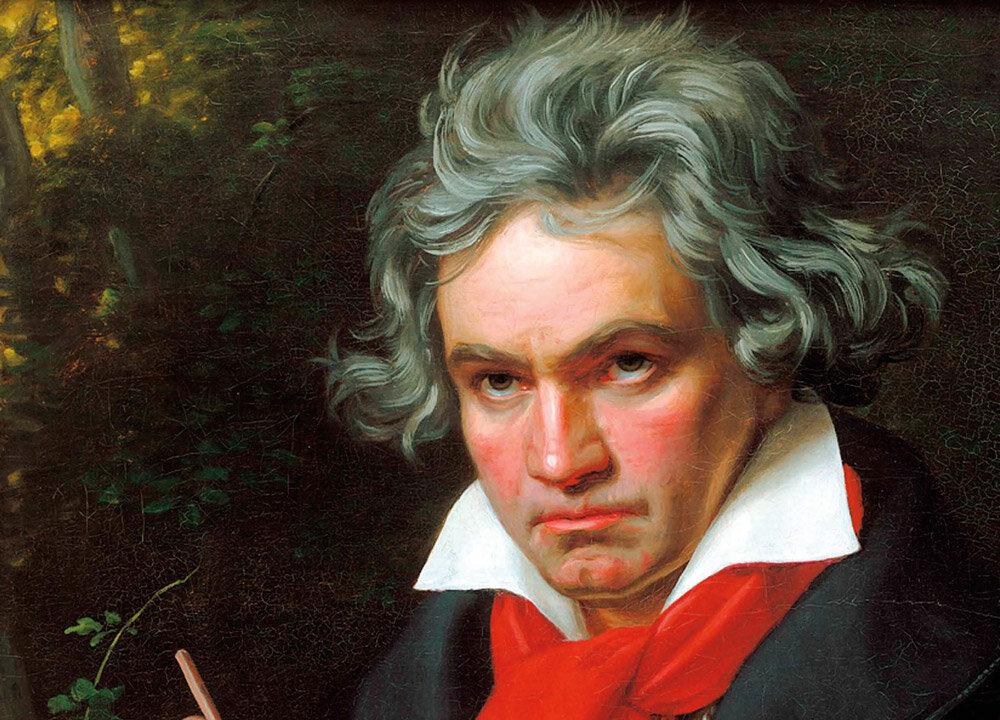

The aim and final end of all music should be none other than the glory of God and the refreshment of the soul.” —Johann Sebastian BachWhen visiting an art museum, you may have noticed that most of the older paintings depict kings, queens, and other nobles, or holy devotional scenes from the Bible. The simple reason, as you may already know, is that prior to the 18th century, the church and wealthy patrons paid for most artworks. One might be forgiven for thinking that “common” people didn’t exist prior to the 18th century, as so few were depicted in the art.

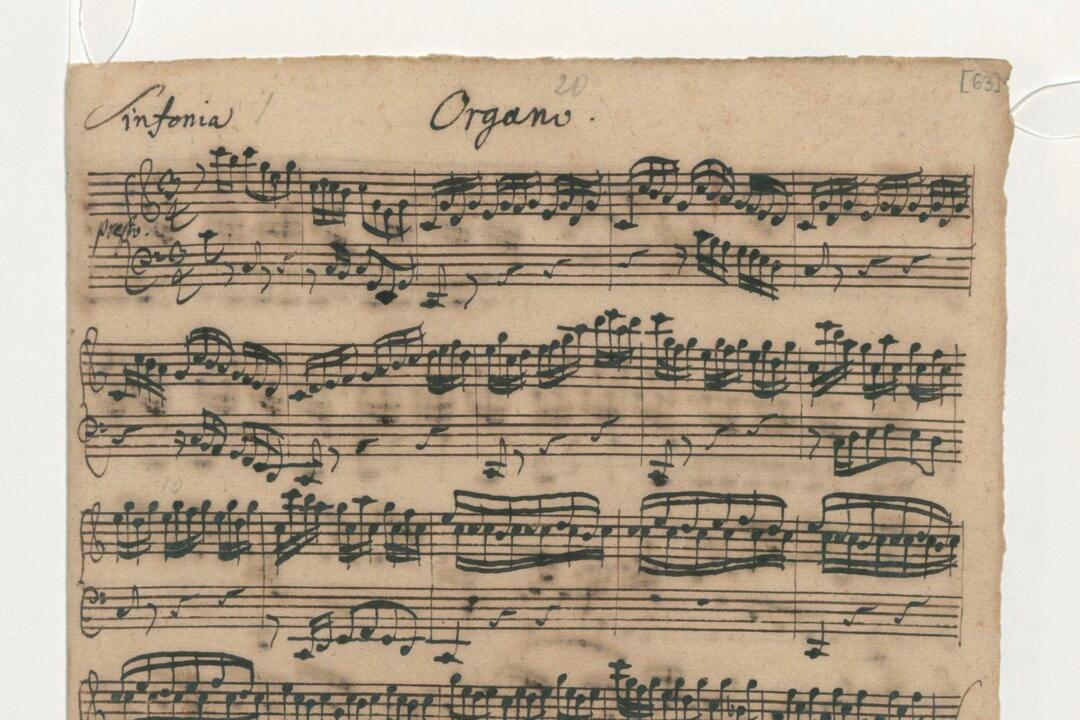

The term “starving artist” was more an actuality than a stereotype, and described composers as well as painters; it isn’t easy to compose for a choir or an orchestra if you can’t pay the band. The Baroque era is littered with choral works, cantatas, and anthems for one king or another, all paid for by the churches and nobility; at that time, artists were mostly constrained by the wishes of their benefactors and patrons. Keep in mind that, in those days, even the paper upon which one would write a music score was a relatively new and expensive innovation. Parchment made from untanned animal skins was a common writing material before the widespread popularization of paper as we know it. One must get beyond the Baroque era before you find artists who were not all “baroke.”