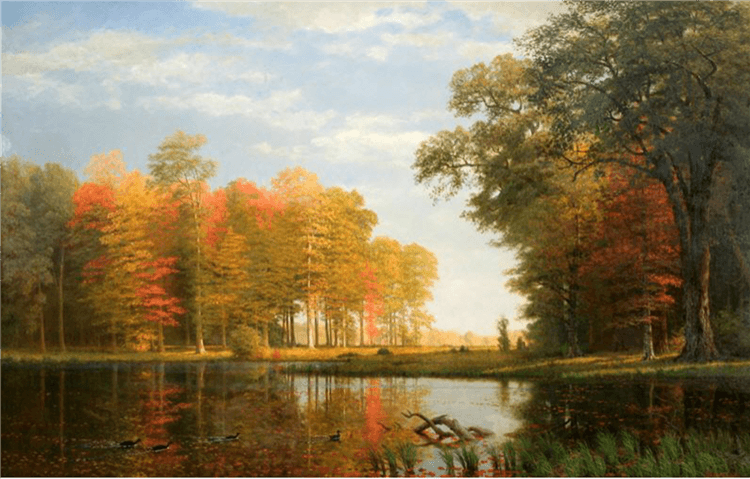

More than any other season, autumn reminds us of time’s passing and of our own transience. Everything about us is in motion; the cascade of leaves, the rapid succession of colors, and the onset of chill evoke time’s passage and mortality. At the same time, there is a delicate balance between the time of abundant harvest and the time of fading and approaching decay.

The natural beauty of the season is therefore an opportunity for reflection on our place in time. Among the many poems dwelling on autumn as an illustration of our mortality, the following poems explore our relationship to time and also demonstrate how natural beauty can stir the soul to the contemplation of higher things.