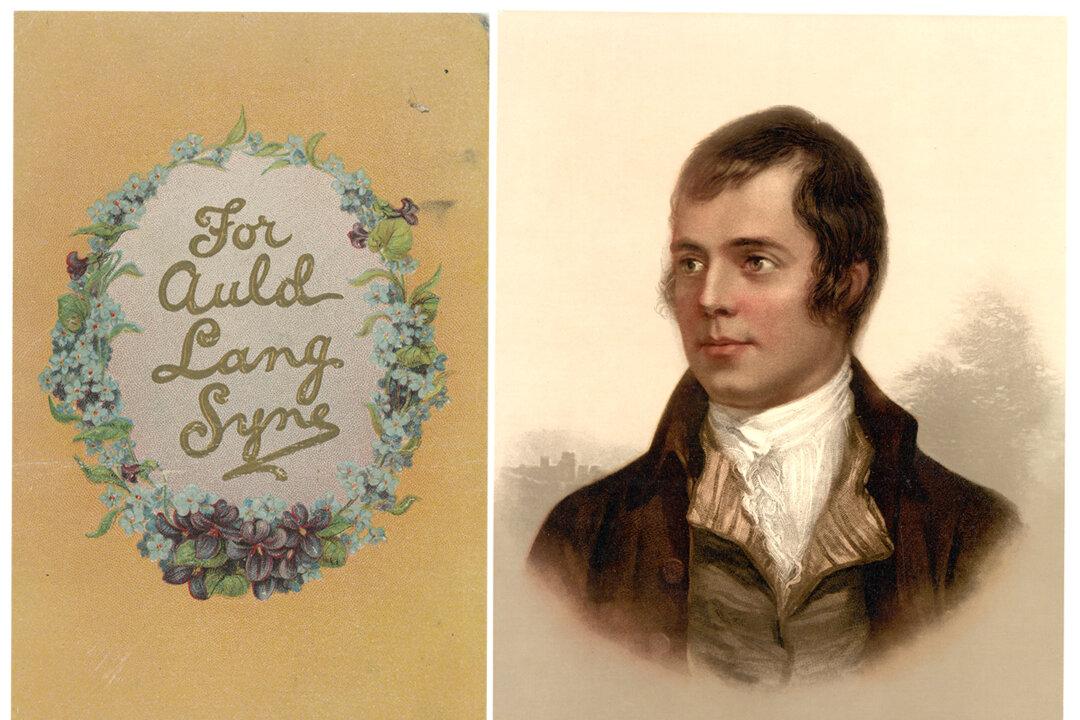

For auld lang syne, my dear For auld lang syne We'll drink a cup of kindness yet For the sake of auld lang syne

Each holiday season, people around the world sing the words to the famous Scottish folk song, “Auld Lang Syne,” as they celebrate the arrival of a new year. Its last verse, listed above, encourages fond remembrance of the past and joy for the future.The singing of the sentimental “Auld Lang Syne” is America’s perennial New Year’s Eve musical tradition. But its creation traces back to Scotland, where a renowned 18th-century poet first penned the verses.