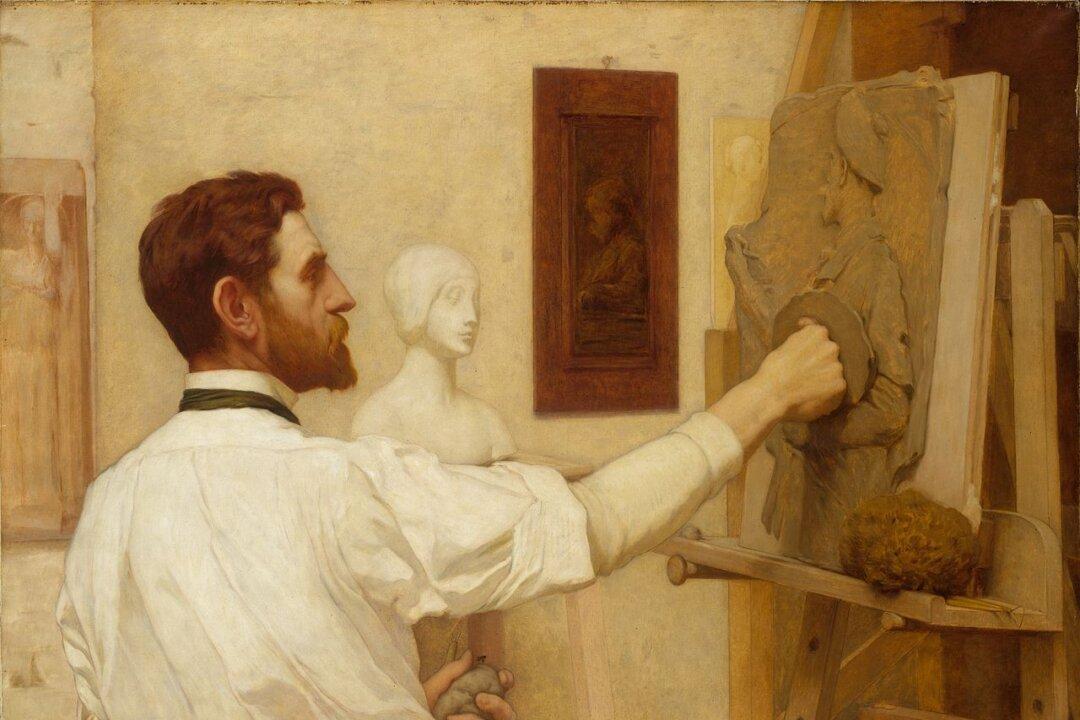

Alongside the Connecticut River amid bucolic hills and mountains lies the western New Hampshire town of Cornish. This small town, home to the world’s longest two-span covered bridge, became famous in the mid-20th century as the place where elusive author J.D. Salinger chose to retreat permanently from New York City. Cornish’s artistic history, though, extends to the late-19th century. Starting in 1885, America’s preeminent sculptor, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, routinely left his New York City residence and studio to spend summers in the cooler clime of Cornish.

Saint-Gaudens's estate (named "Aspet") at the Cornish Colony in Cornish, N.H. National Park Services. Public Domain