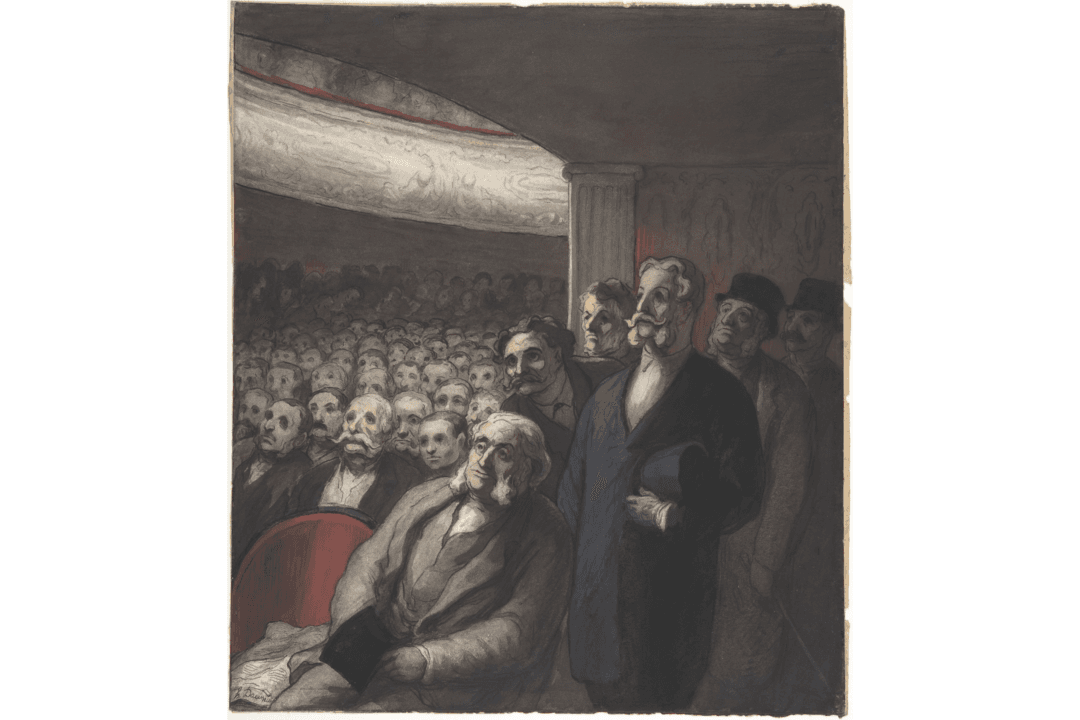

Why don’t more people go to the theater?

It’s no secret that theater participation plummeted during the pandemic and hasn’t recovered to its prepandemic level. Recent studies have shown that adults 35 and over are attending theater rarely, if at all. According to a recent article in The New York Times, Broadway attendance is down almost 20 percent from the prepandemic era.