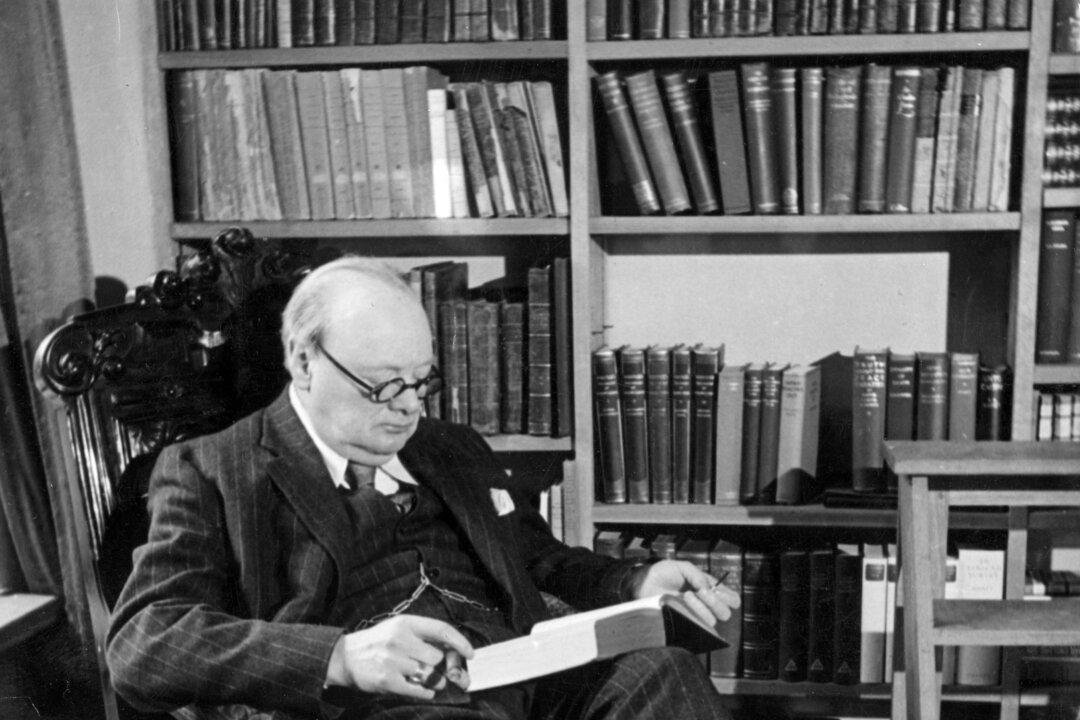

Most of us know Sir Winston Churchill’s very public persona—a man of great charisma, achievements, and vision. Chartwell House, the Churchill family’s country home, offers visitors a hint of how Churchill and his family lived behind closed doors.

Churchill lived at Chartwell from 1922 until October 1964, a few months before he died on Jan. 24, 1965. Katherine Carter, project curator at Chartwell, shared in a phone interview more about Churchill’s time at Chartwell.