During the recent appearance of the northern lights, multitudes of people drove out into the countryside, far from the city lights, to get a better view of the skies. In seeking out the dark, they were afforded a better view of the beautiful ribbons of lights spanning the sky.

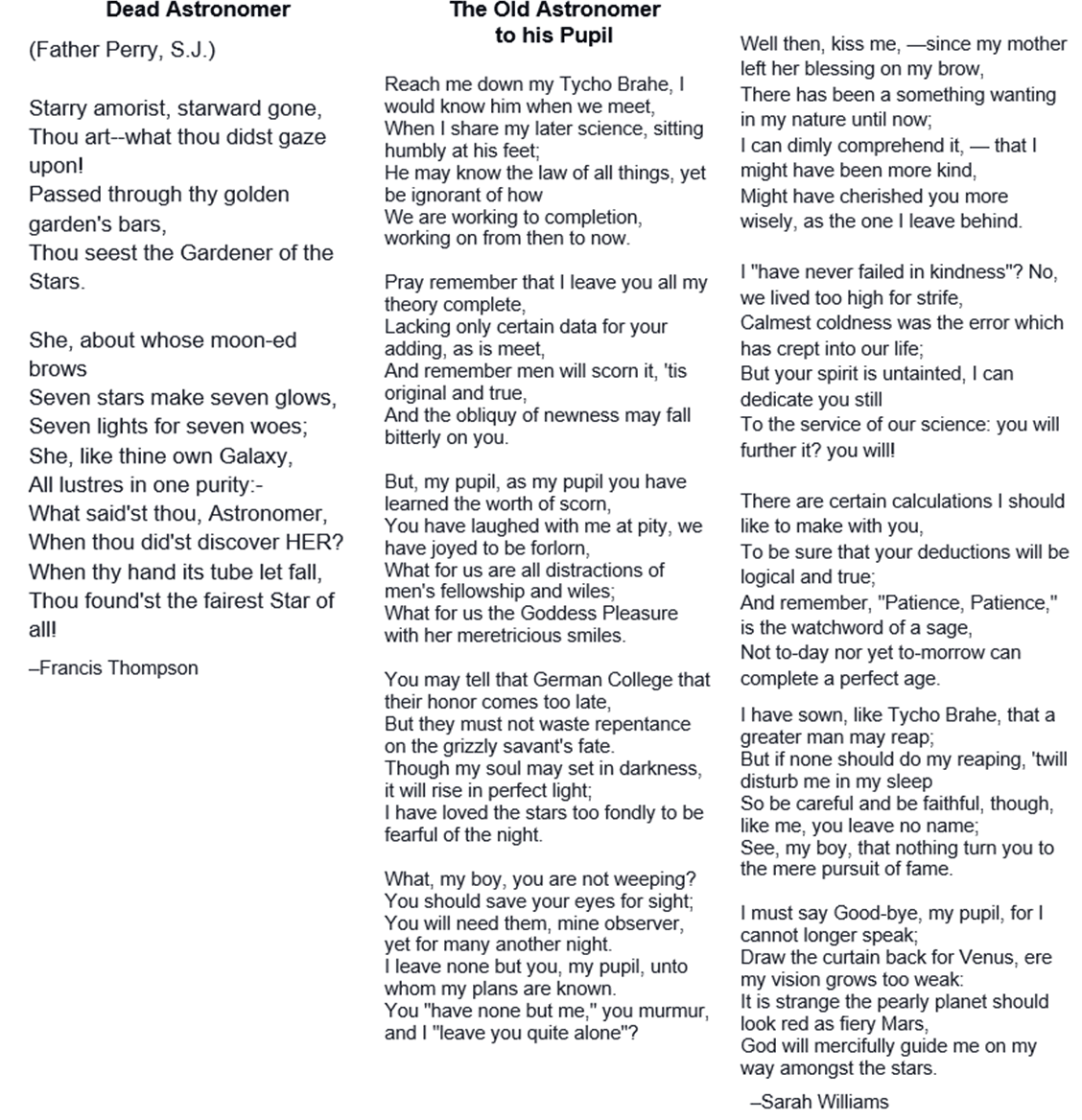

Astronomers in the Poetry of Sarah Williams and Francis Thompson

Two 19th century poets reflect on the beauty of the stars in the night sky.

The astronomer's studies of the heavens feature prominently in poems by Sarah Williams and Francis Thompson. “The Astronomer,” 1668, by Johannes Vermeer. Public Domain