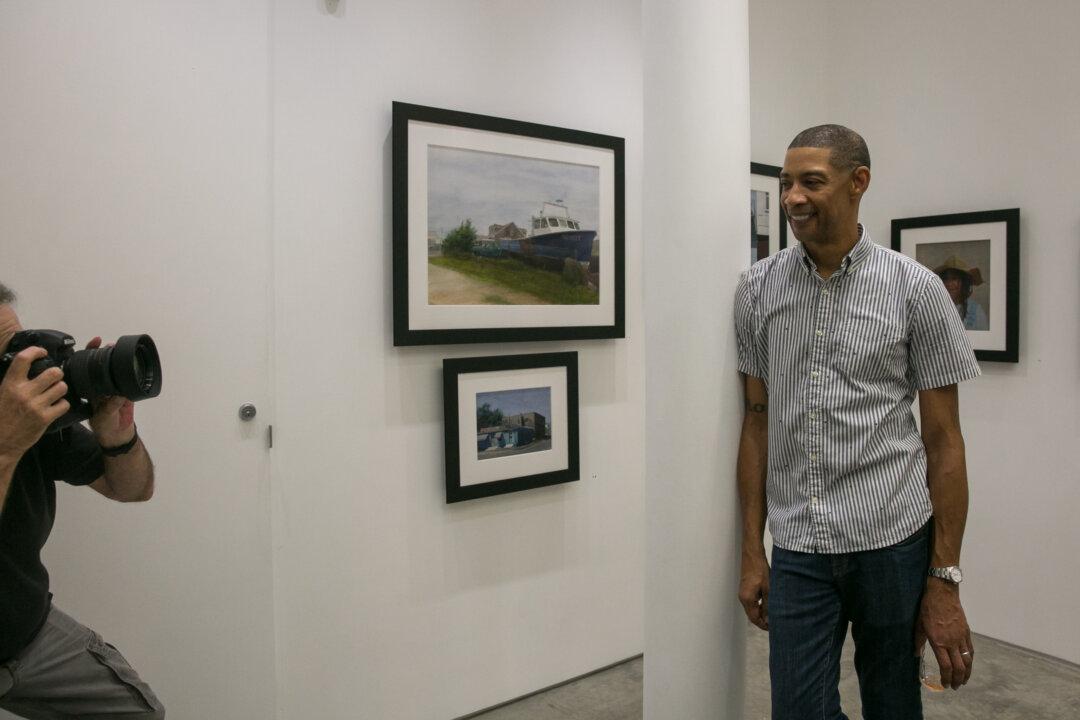

NEW YORK—How could it be possible to convey the poetry, the depth, the sweat, the soulful interpretation of life in the watercolor paintings by Mario Andres Robinson? The essence they emanate can only be fully appreciated in person, because they are the results of countless moments transformed into multiple thin layers of paint. The washes and glazes he applies to render a beautiful luminosity is a testament to the love of the people and places he has immortalized on paper made of cotton rag and linters.

The great American realist artist Andrew Wyeth once said, “One’s art goes as far and as deep as one’s love goes.”

This truism is immediately evident in Robinson’s paintings.

Robinson paints people and places he knows well and has known for a long time, revealing their layers of character and emotion. His paintings tell open-ended stories of his family, close friends, and a few interesting acquaintances in their usual settings. He renders these average Americans extraordinary. To him, they are heroes; to the viewer, they are strangers. Yet, because of Robinson’s honesty and passion for what he does, the way he conveys their humanity with paint is enthralling.